A Royal Invoice

Tiny Town Sparks a Global Fascination

In April 1924, King George V (1865-1936) opened the British Empire Exhibition in Wembley to revive a war-weary economy. The 215-acre trade fair and amusement park showcased the resources of his Empire, uniting fifty-six colonies and dominions in a bid to boost prosperity and trade networks. Australia’s pavilion was abuzz, boasting dioramas with life-sized butter sculptures, faux apple orchards, cardboard cutouts of cattle, artfully arranged coal, frozen beef, a brass band, and live sheep shearing displays.

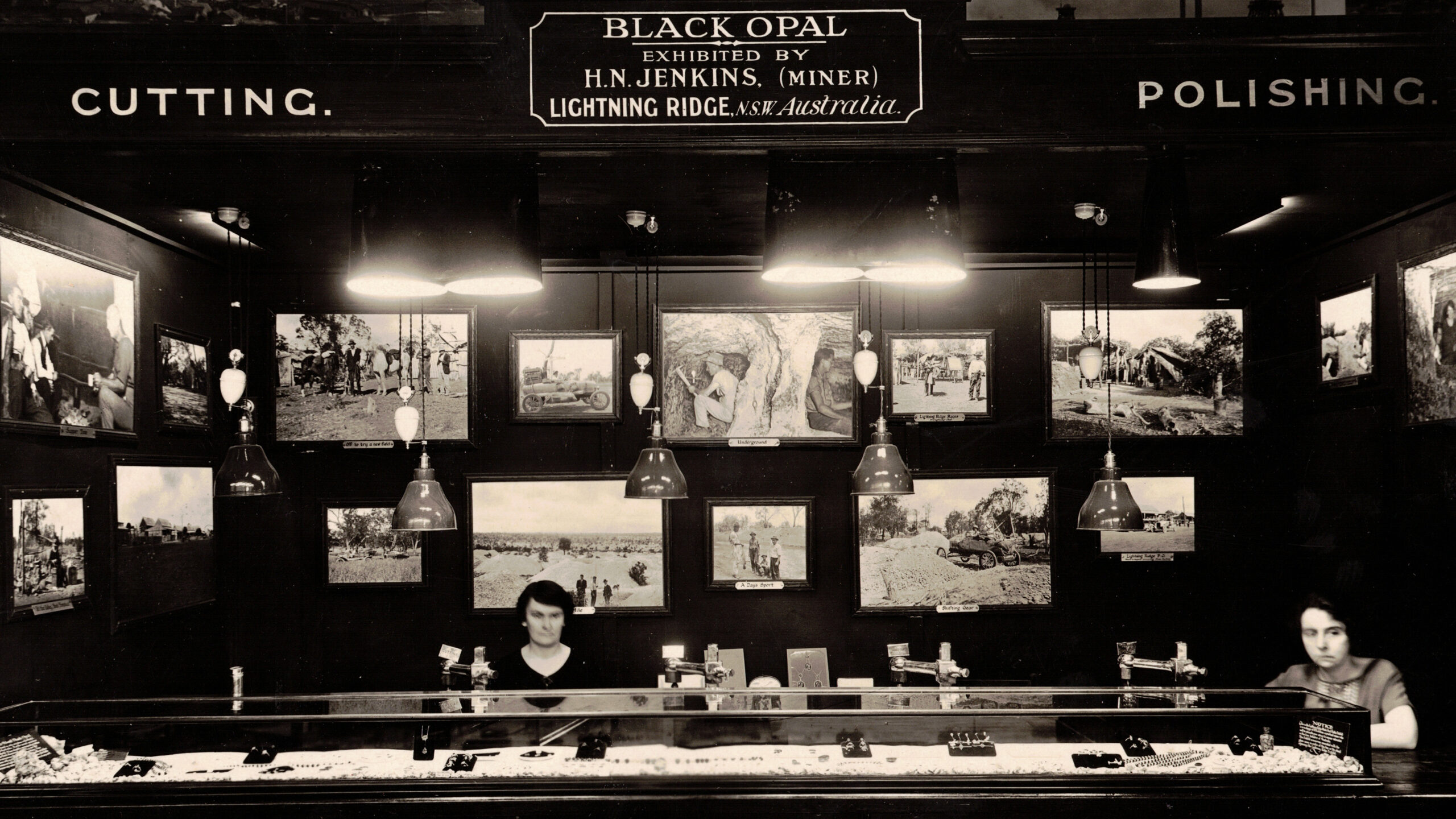

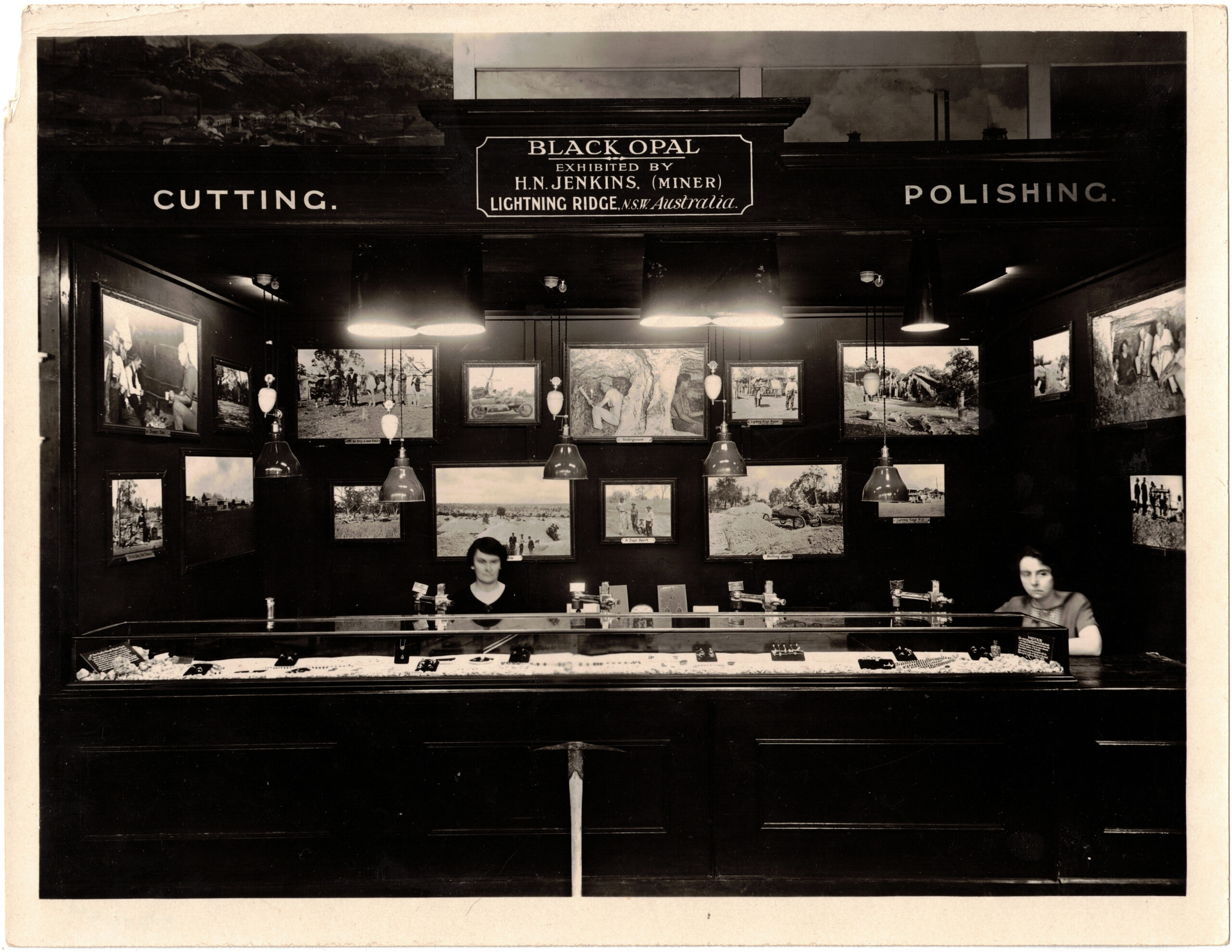

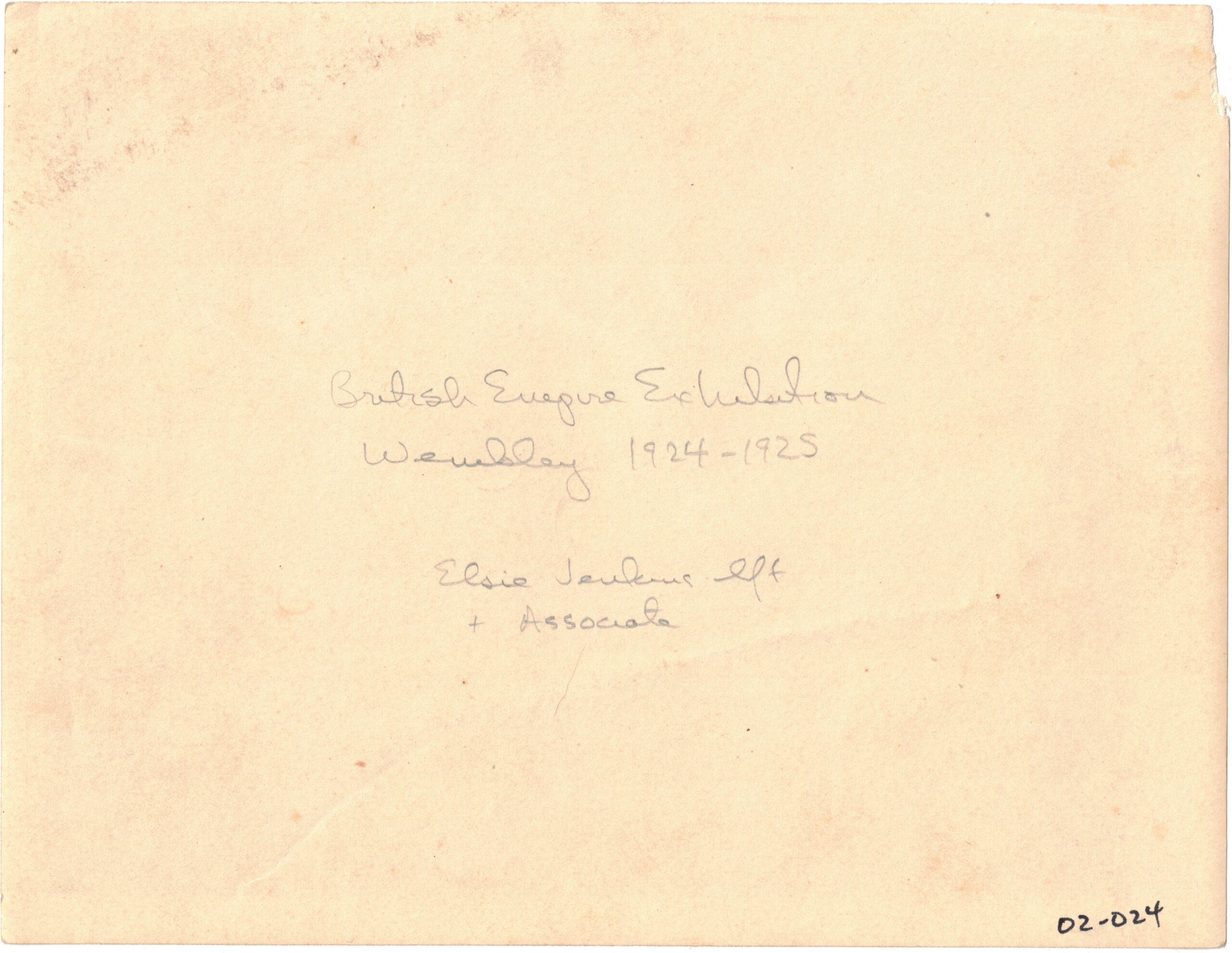

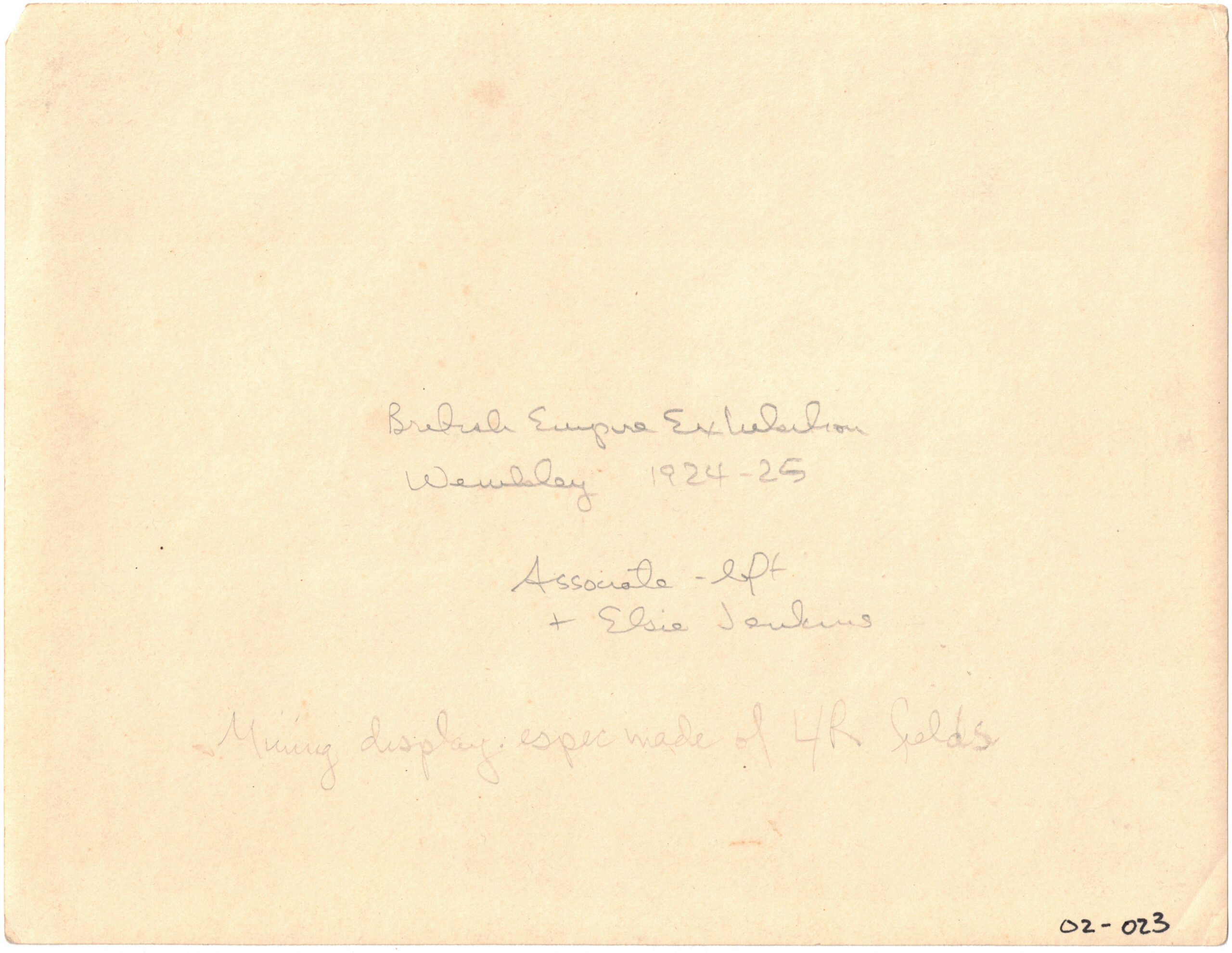

Spanning two six-month seasons in 1924 and 1925, an astonishing twenty-seven million people enjoyed the rides and exotic displays of commodities and industry. Outback power couple, Hector Jenkins (1884-1953) and his wife Elsie (1887-1974), presided over promoting black opals from Lightning Ridge in the Australian pavilion, introducing kings, queens and commoners alike to the rare stones.

Known as ‘Tiny Town’ because they were both barely five feet tall, the Jenkins’ arrived in Lightning Ridge to mine opals in 1918, but Hector, a gemmologist, soon saw more promise in marketing the gems. Six years later, the couple’s display at the British Empire Exhibition helped put black opals on the radar globally.

Up to 70,000 visitors a day for two people used to living in the outback must have been gruelling. When Queen Mary (1857-1953) admired an opal during her visit and asked if she could have it, Elsie obliged but was clearly miffed by the brazen request. She later asked the exhibition’s Director where she should send the bill. The response that no one bills royalty was grist for Elsie’s mill, undaunted, she sent an invoice to Buckingham Palace and received payment.

Not just a promoter of opals, Hector was also their self-appointed protector. Hansard documents a cablegram he sent in 1925 about a Birmingham jeweller selling fake opals at the exhibition. His claim prompted requests in the House of Representatives that the Minister for Markets and Migration ‘…ensure that the great Australian industry of opal mining is not injured by faked opals being sold.’

While the couple may have been small in stature, they weren’t afraid to dream big and commit to their vision of bringing what was to become Australia’s national gemstone to global markets.