Capturing the Barrier

James Wooler's Broken Hill

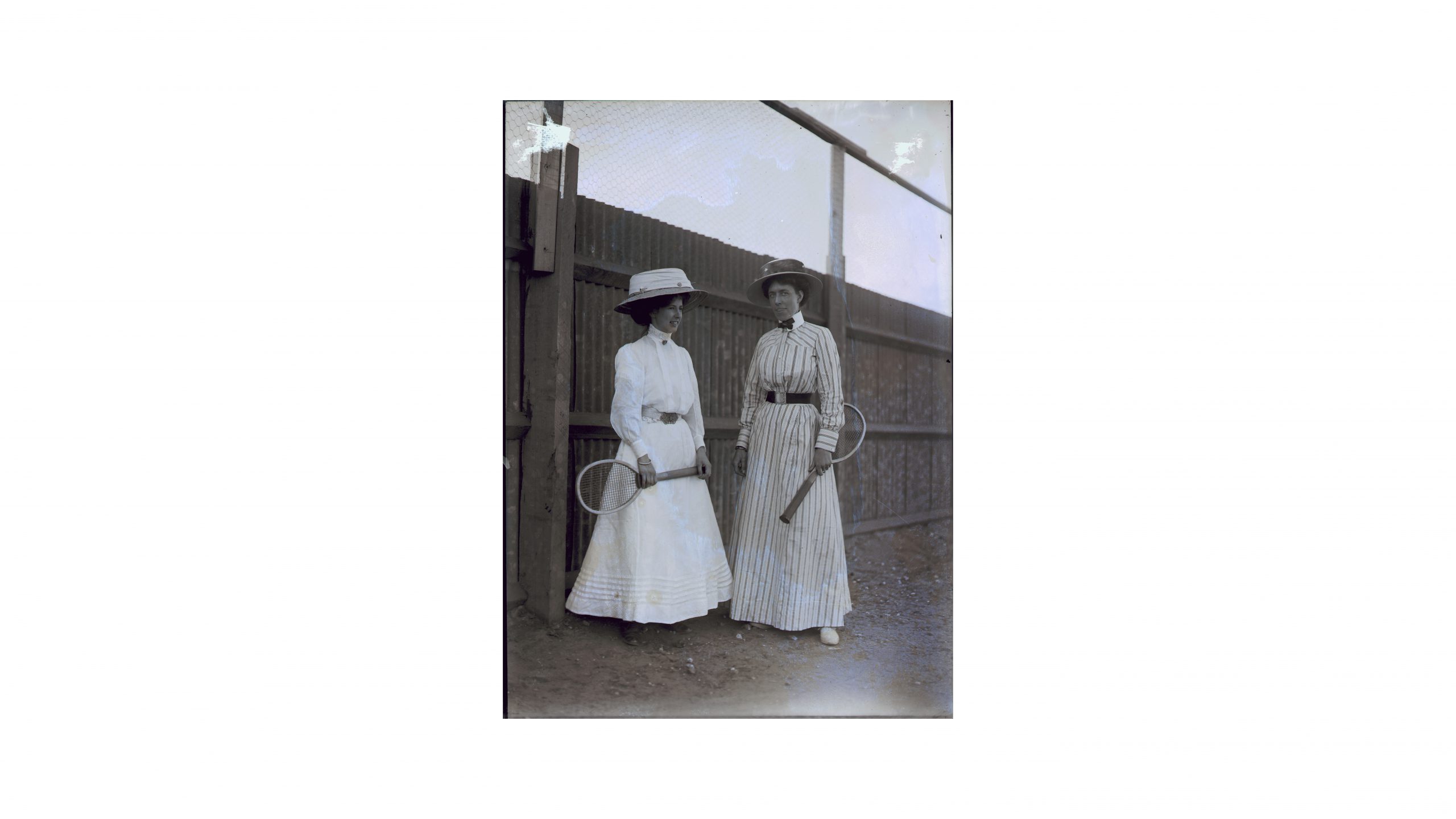

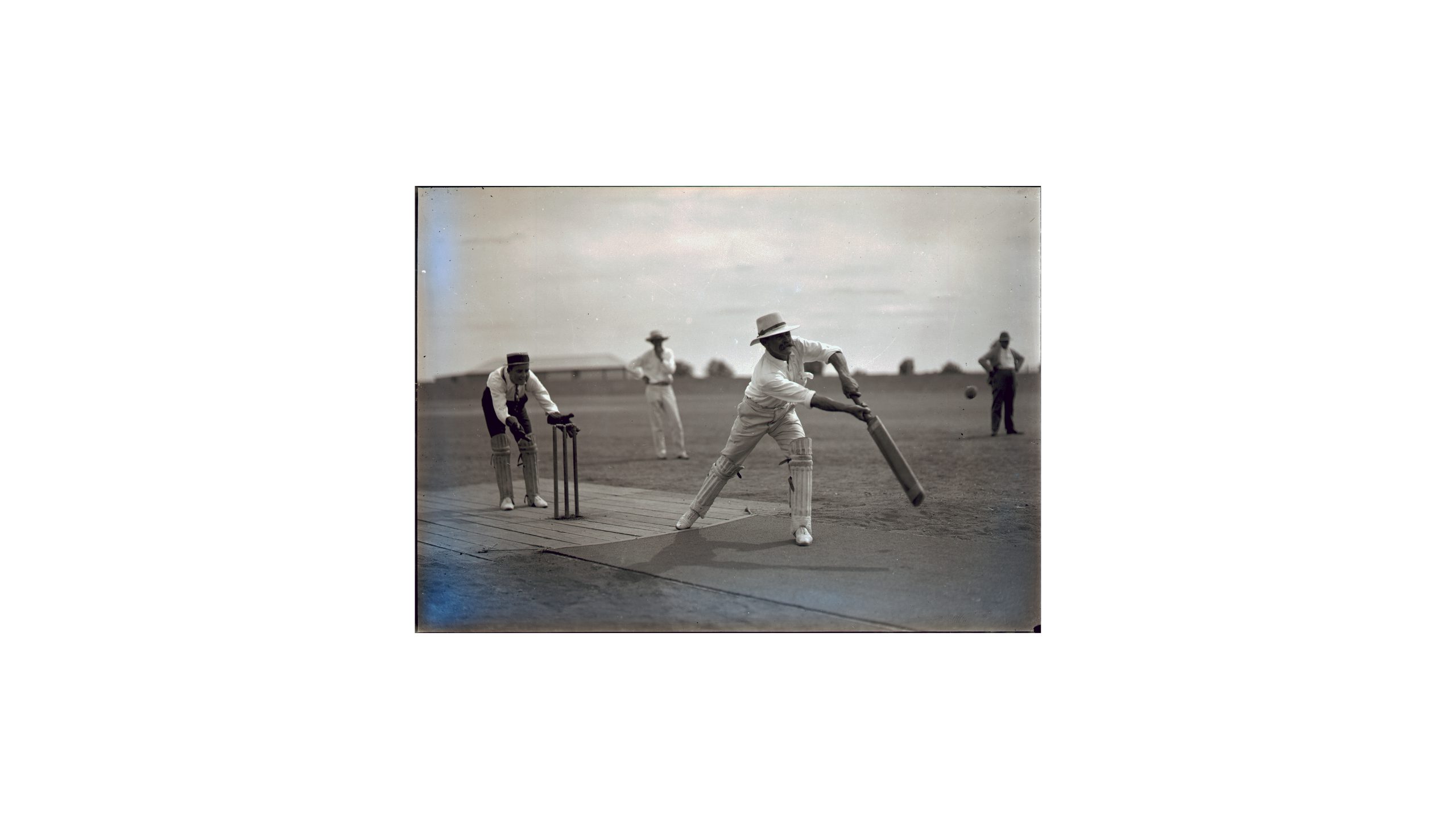

Although James Wooler (1872-1944) resided in Broken Hill for only a few years his photographs transformed how the world saw its people. His work for The Barrier Miner put the newspaper at the cutting edge of mass media, surpassing The Age and the Sydney Morning Herald’s ability to illustrate articles. His photographic legacy is a graphic insight into the lives of working class people in an outback town in the early 1900s.

James was born in Yorkshire in 1873, he was one of fourteen children and worked in the local mill part-time from the age of ten to help support his family. He had an interest in art from an early age and painted with oils. It is not known when he took up photography but his working class background fostered his ability to approach his subjects sensitively.

Photography was an ideal pathway for James’ creativity and yearning for a job that did not tie him down. He married Alice Waterton (1873-1971) in 1898 and worked as a baker while he built his photographic career part-time. Alice’s family lived in Broken Hill and the couple migrated to Australia in 1907 to be closer to them.

The outback weather and landscape came as a shock to Wooler. A huge dust storm engulfed the town soon after their arrival and James was selling photographs of the storm as postcards within days. He worked on the mines while he built up his photographic business and by 1909 he had become the official photographer for The Barrier Miner newspaper.

James’ photographs focused on the lives and leisure of working class people, and he did so with sensitivity. His photographic ability transformed the newspaper. He taught himself how to manufacture half tone blocks, which sped up the print process and enabled more photo features to be printed. He also used bromide paper, which brought a sharpness to his prints that was absent in the work of other local photographers.

When the Woolers left Broken Hill in 1911 the abundance of photographic features in The Barrier Miner subsided. James left behind a substantial collection of glass negatives that captured a tumultuous three-year window on daily-life in the heavily unionised mining town.