Life in the Shadow of the Hydrogen Bomb

The Immediate Effects of a Nuclear Event

‘If Soviet Russia has the hydrogen bomb… then the West must turn again to its defences.’

Published in the Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners Advocate in 1953, this foreboding warning came in response to the Soviet Union’s explosion of their first thermonuclear weapon—a hydrogen bomb. Soviet Chairman Georgy Malenkov considered this the end of the United States monopoly of the weapon and so international tension was only growing.

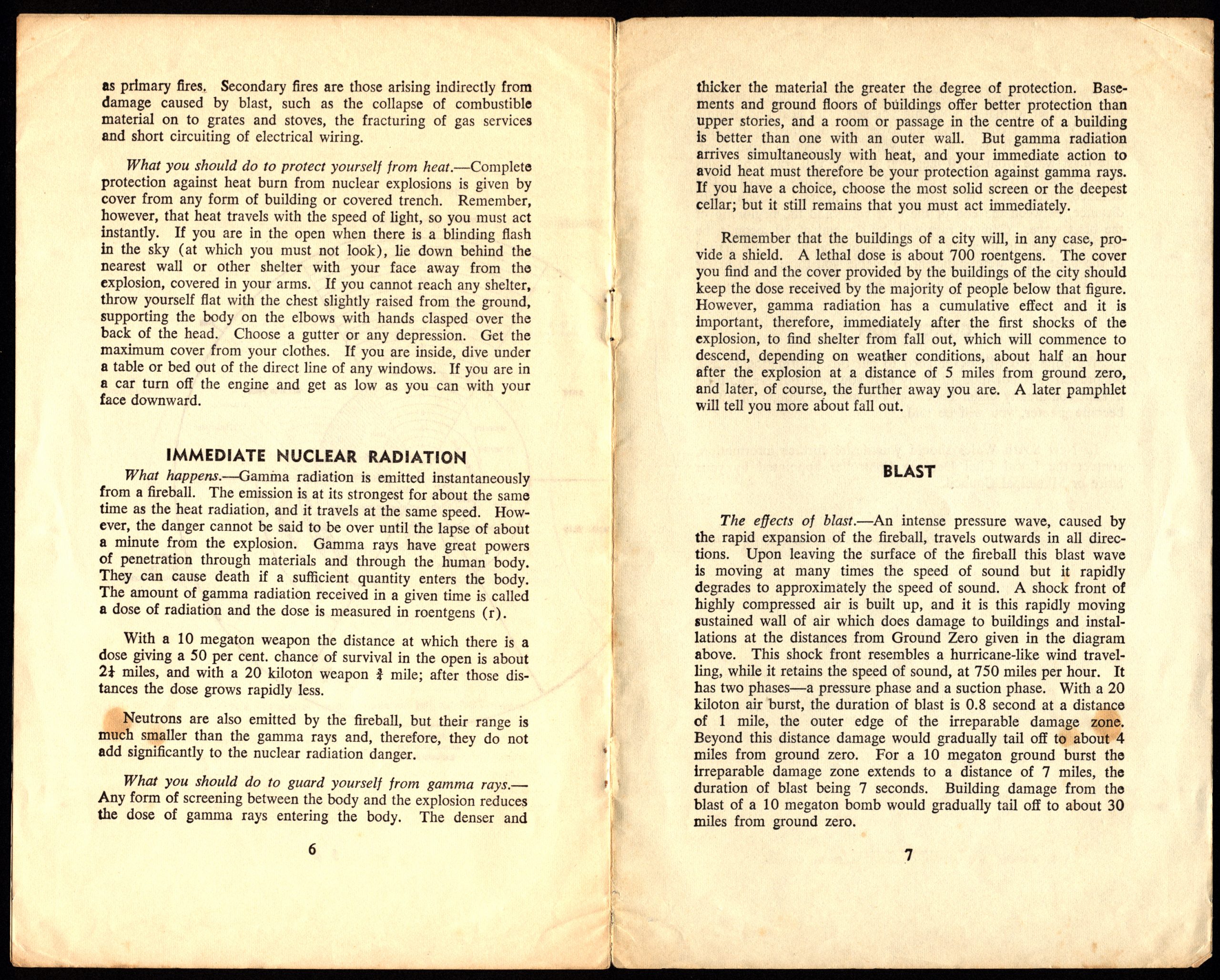

During this era, cities across the world, particularly in the major cities of Allied nations, developed civil defence organisations. As noted in this pamphlet, civil defence organisations, run by a Local Civil Defence Controller (appointed by the Shire or Municipal Council), sought to provide information to prepare the public for any eventual incidents in their city. They would also oversee rescuing the trapped, locating casualties, and caring for survivors.

Alongside Sydney and Wollongong, Newcastle was believed to be at a higher risk of being targeted in a conflict. As a key industrial zone, coal district, and port city, as well as one of Australia’s larger cities, procedures needed to be put in place.

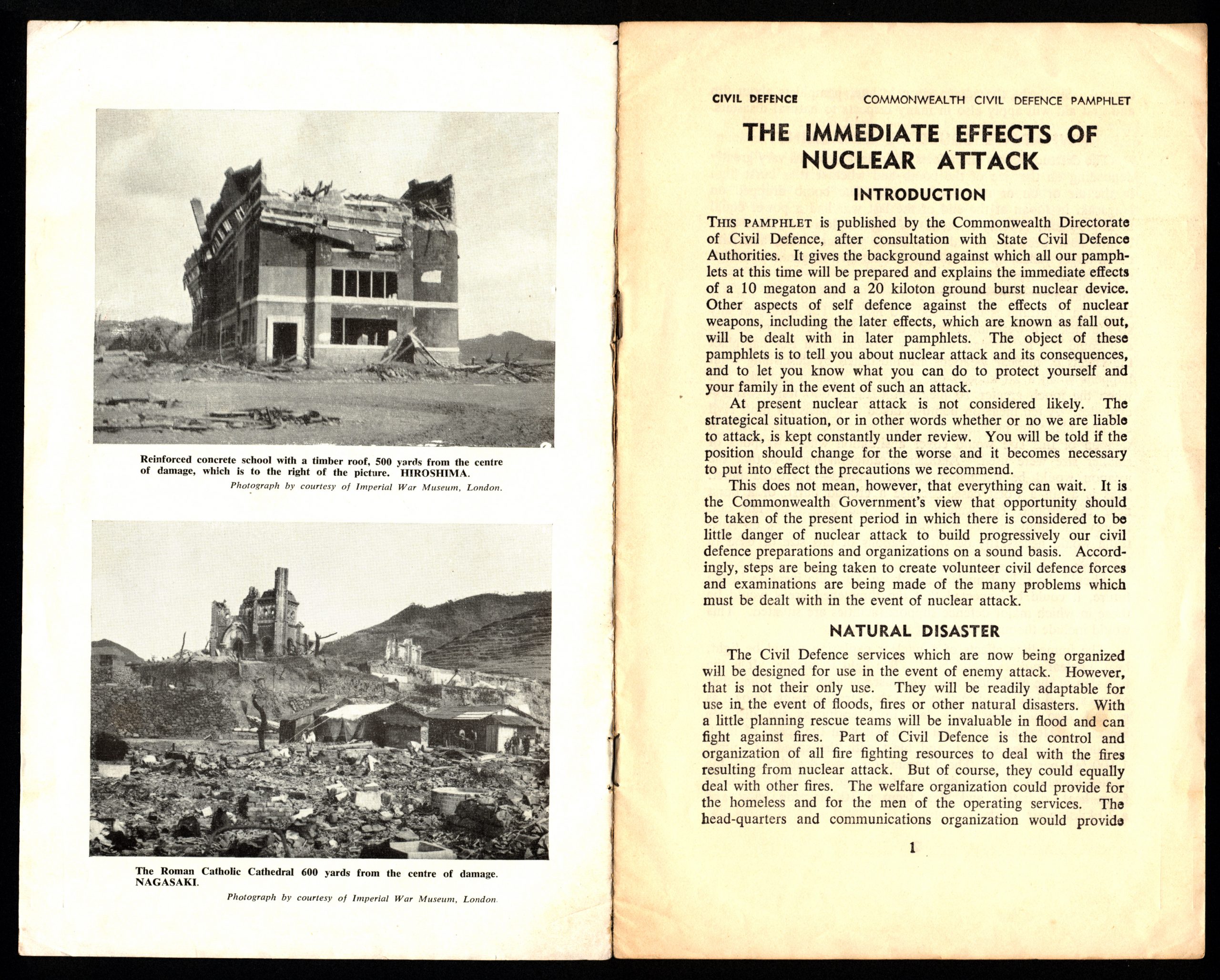

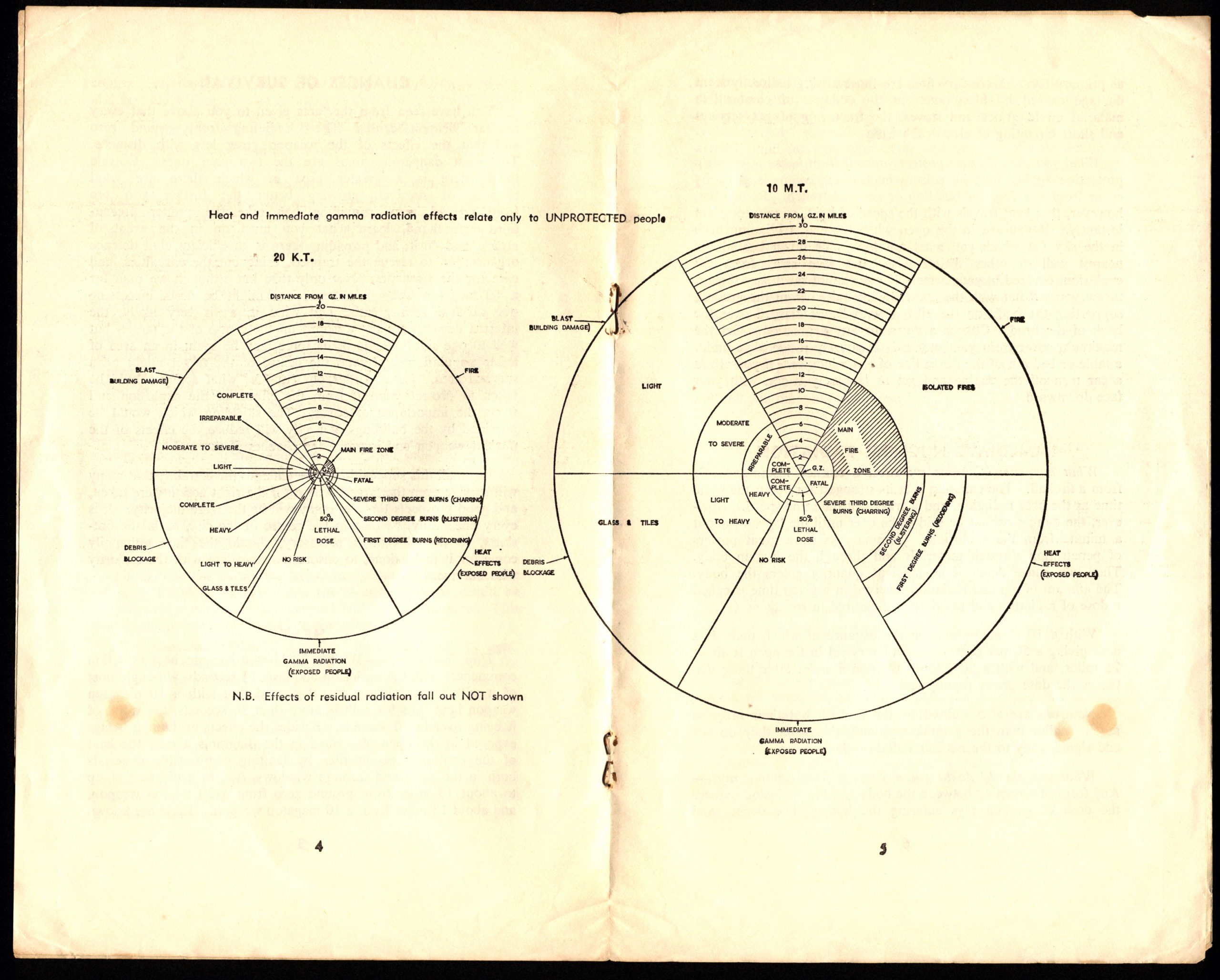

In saying that, the effects of the heat and radiation from the much anticipated 10 megaton hydrogen bomb would cause destruction (complete to light depending on proximity to ground zero) to everything within a 30-mile radius.

The irony of such awareness raising and preparatory measures was that the more informed the general population became, the more hopelessly inadequate – even futile – these organisations felt in the face of such a nuclear event.