The Price We Pay

Reporting on the Hunter’s Floodplain

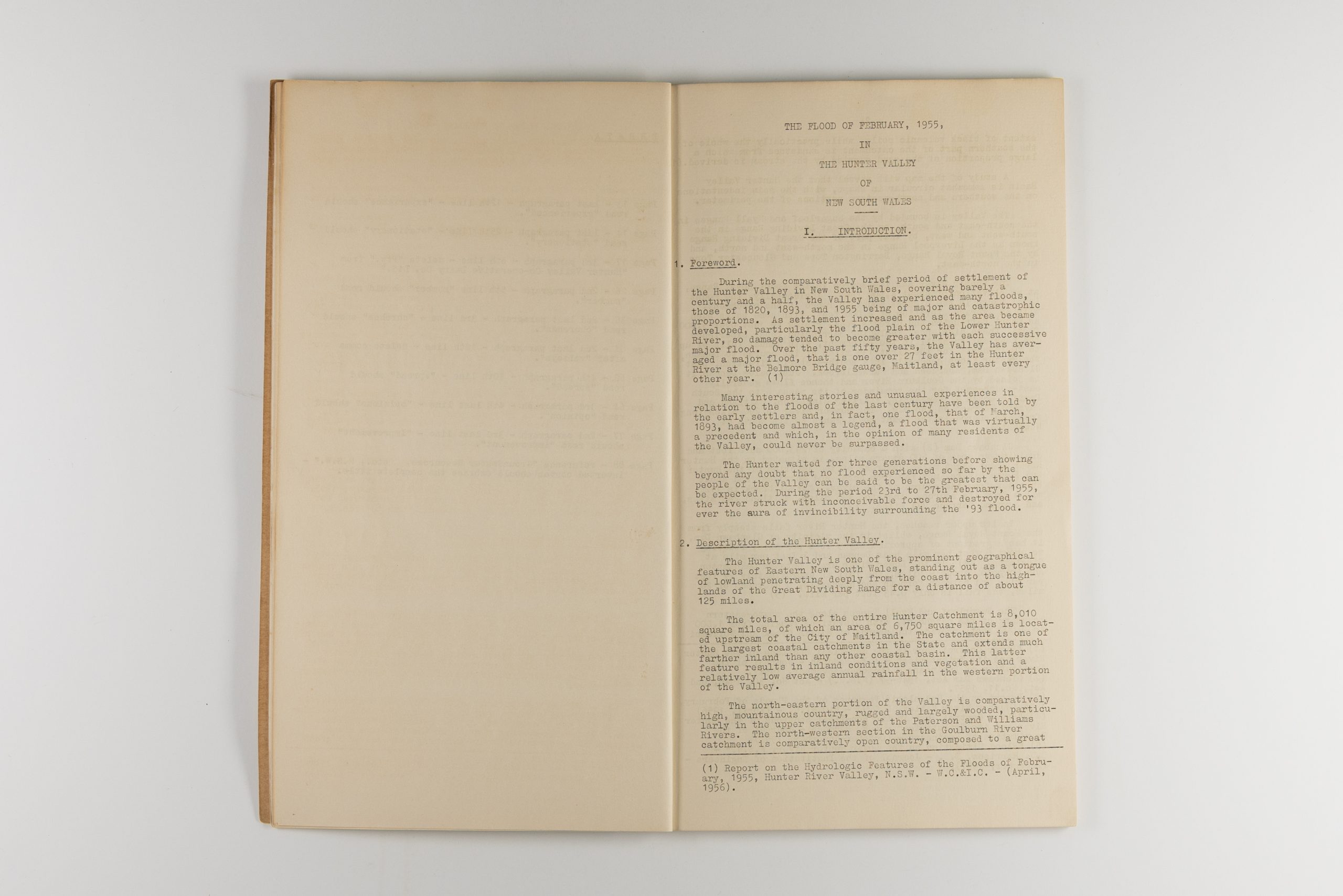

In 1958 William Charles Hawke carried a heavy responsibility. Three and half years had passed since the catastrophic Hunter Valley flood, which had been among the worst natural disasters in Australia’s recorded history. Twenty-five people had died. As Secretary of the Hunter Valley Conservation Trust, tasked with coordinating the work to mitigate flood impacts, Hawke was required to document the 1955 flood and its aftermath. From his office on the first floor of the Maitland Town Hall, he penned A report on the Flood of February, 1955 in the Hunter Valley of New South Wales. But this was not just a collection of data – Hawke had some clear messages to convey to his readers.

Born in Cornwall, William Charles Hawke (1915-1970) migrated to Australia in 1920 and settled in Dungog. Graduating in Law from the University of Sydney, he developed knowledge of rural life and infrastructure while working for the Farmer’s Relief Board and the Forestry Commission.

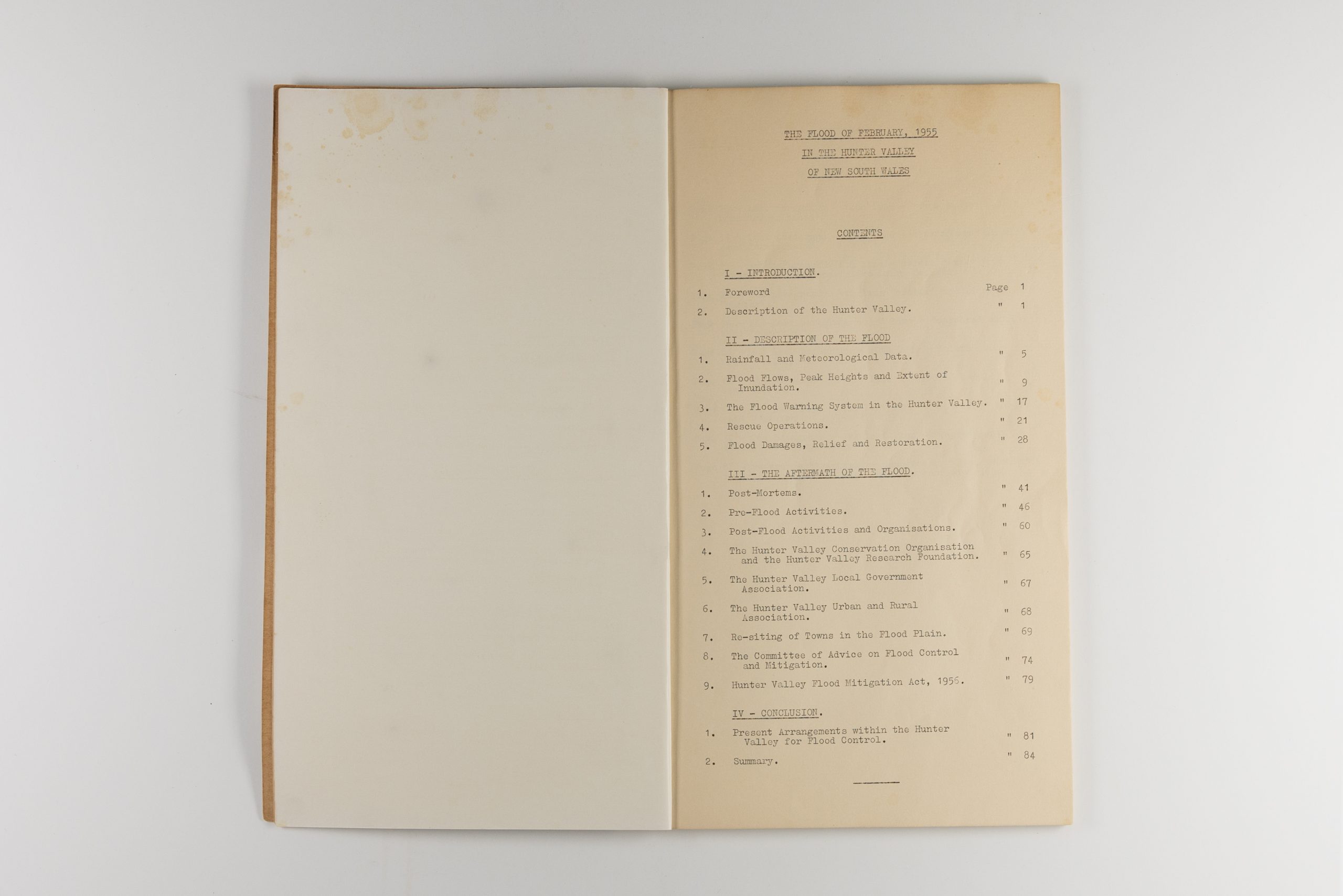

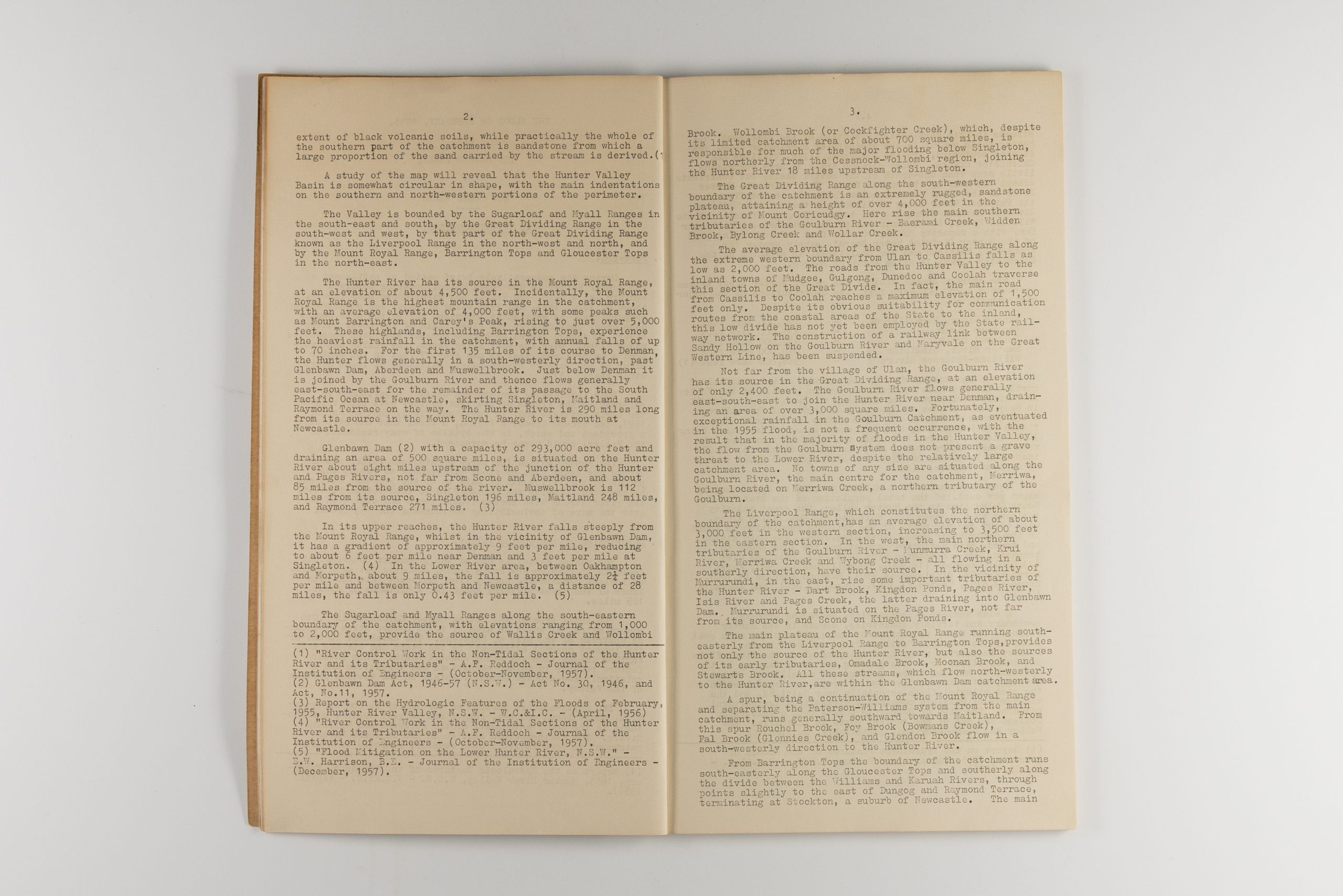

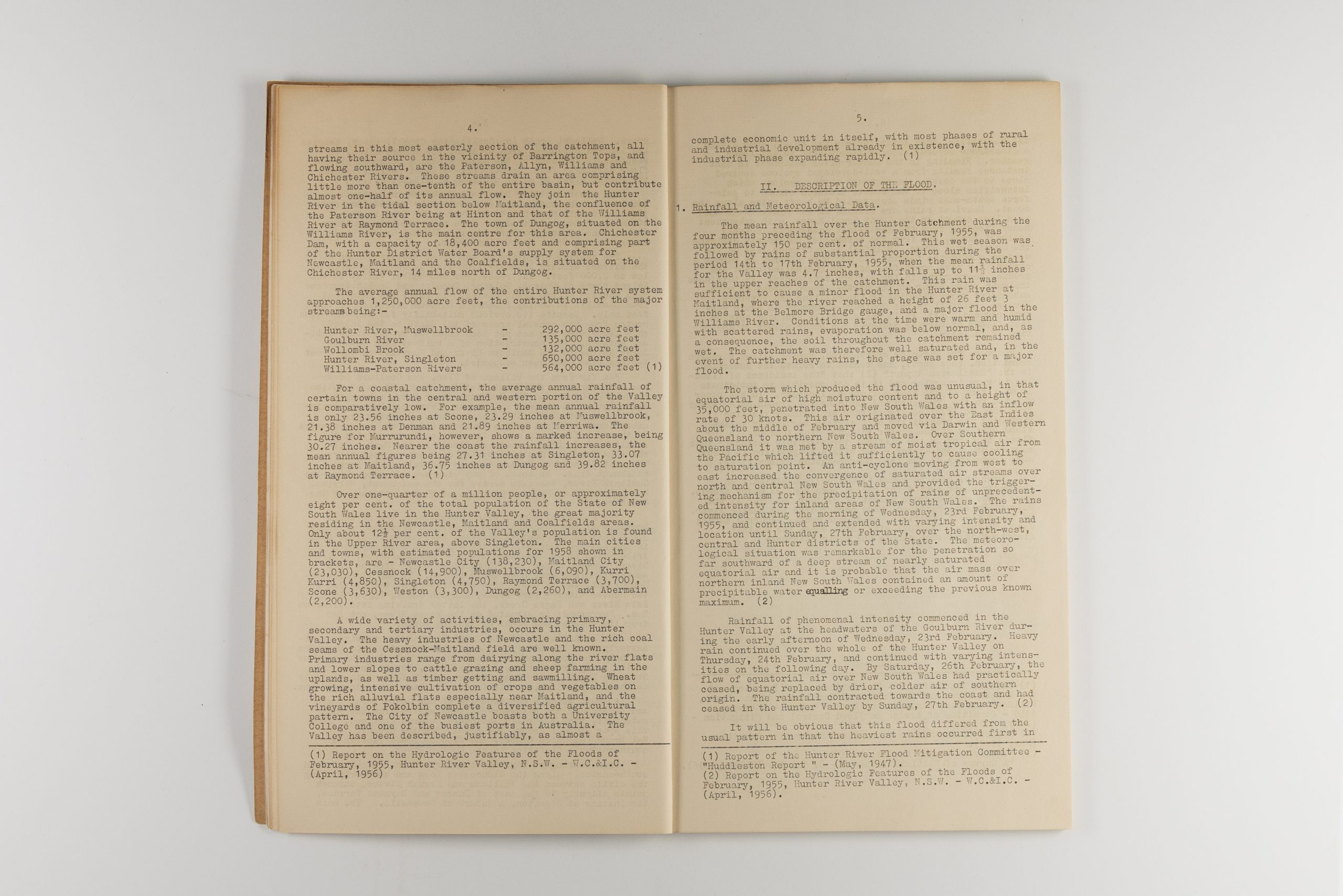

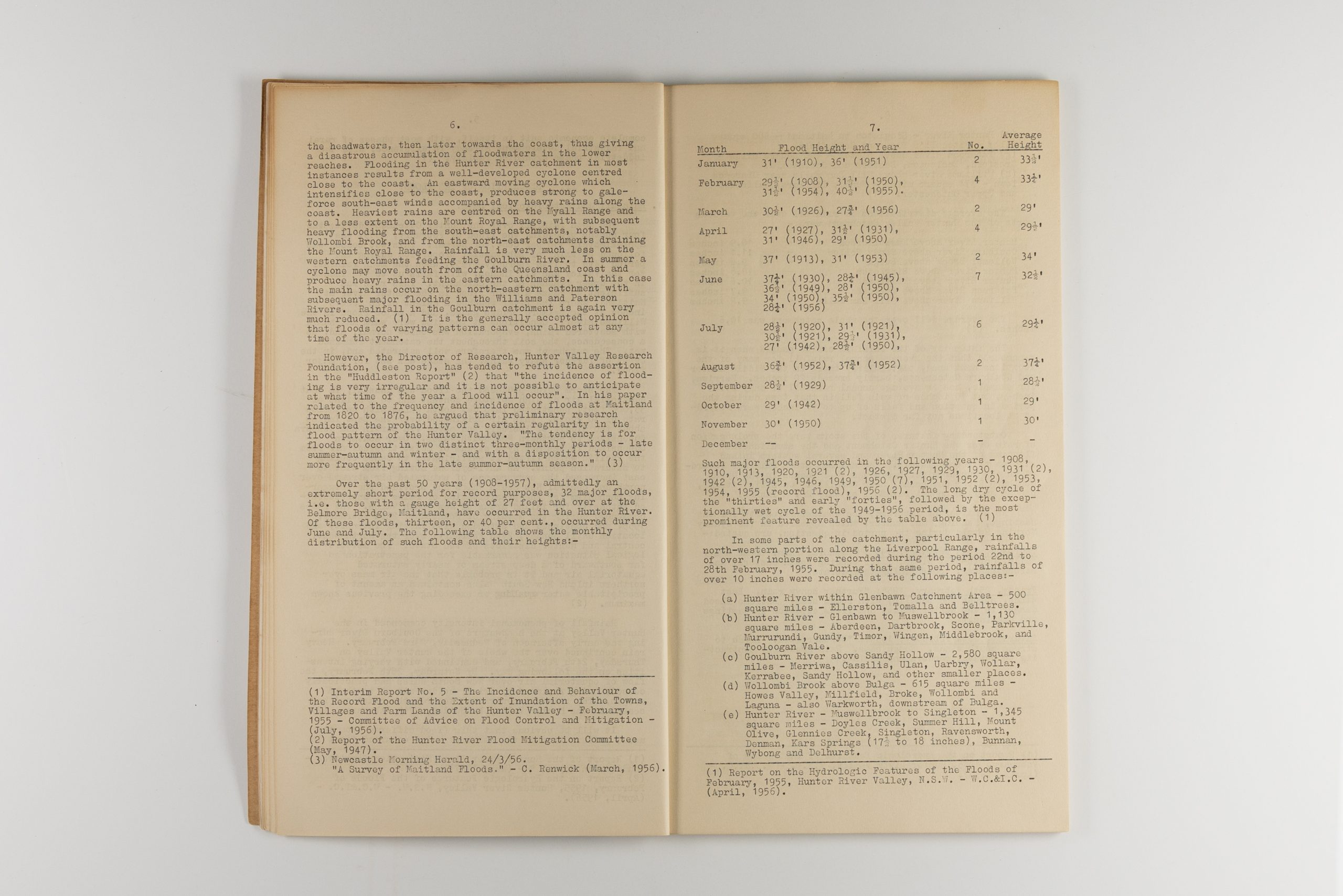

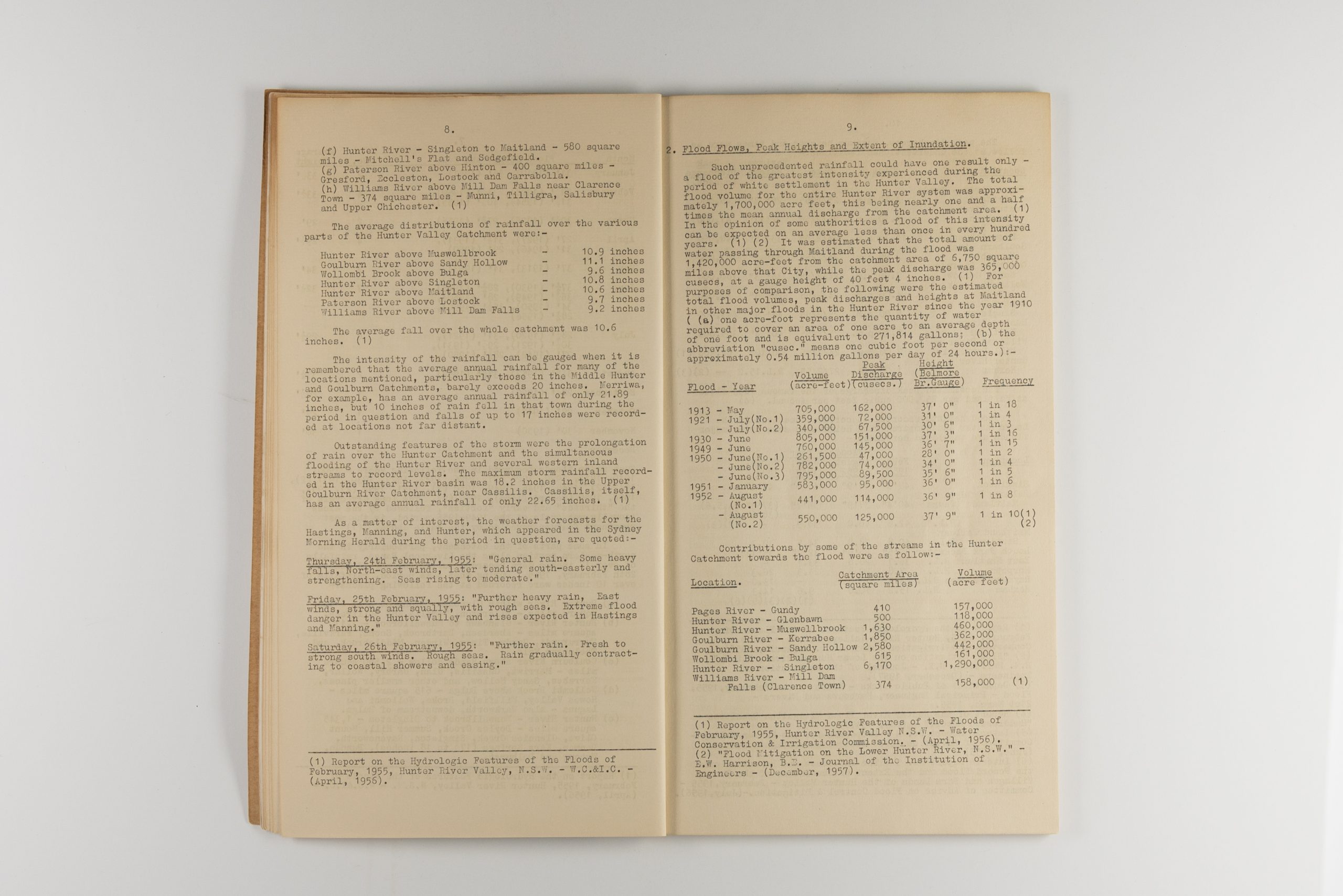

The Hunter Valley has always been prone to considerable flooding and the authorities knew that future devastating inundations were certain. Flood reports were needed to keep the Trust’s members informed and to assist with future life-saving flood mitigation work. Packed with crucial data about rainfall, flood flows and peak heights, Hawke’s report meticulously described the flood and its impacts, including all the dreadful details of the post-mortems of those who had drowned, and the challenges faced towards recovery.

But Hawke reported his findings that the multiple organisations involved in the clean-up, each with conflicting approaches, had only created obstacles for the effective paths to recovery. And bluntly reminding his readers of the stark reality, Hawke noted that damage should be expected if we choose to live in the natural path of floodwaters. Flood control comes at an environmental and economic cost, he wrote, concluding that, ‘The cost of this protection is the price we pay for occupying the flood plain’.