Under the Skin

The Plastic Cadaver of Glen Innes Hospital

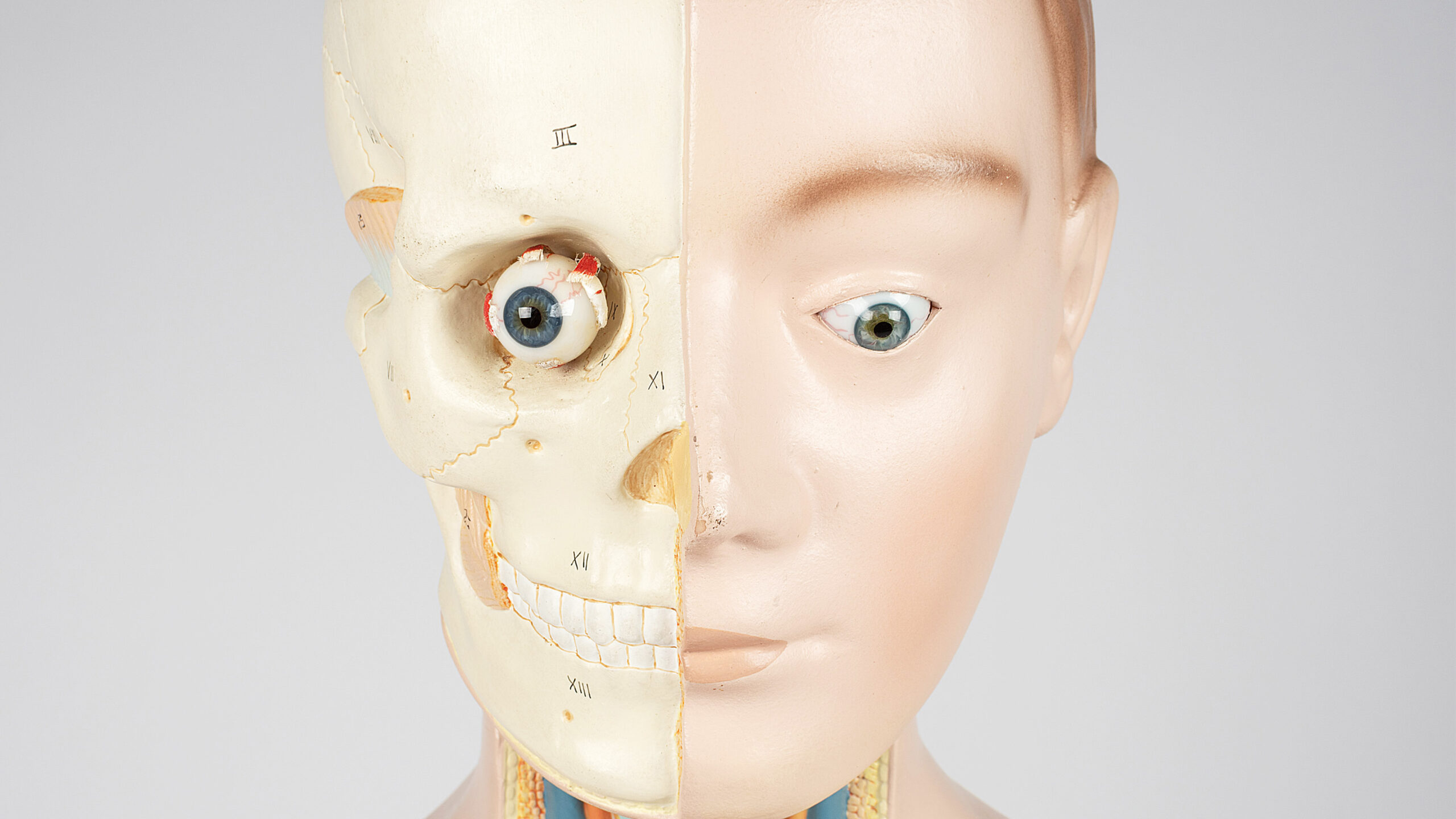

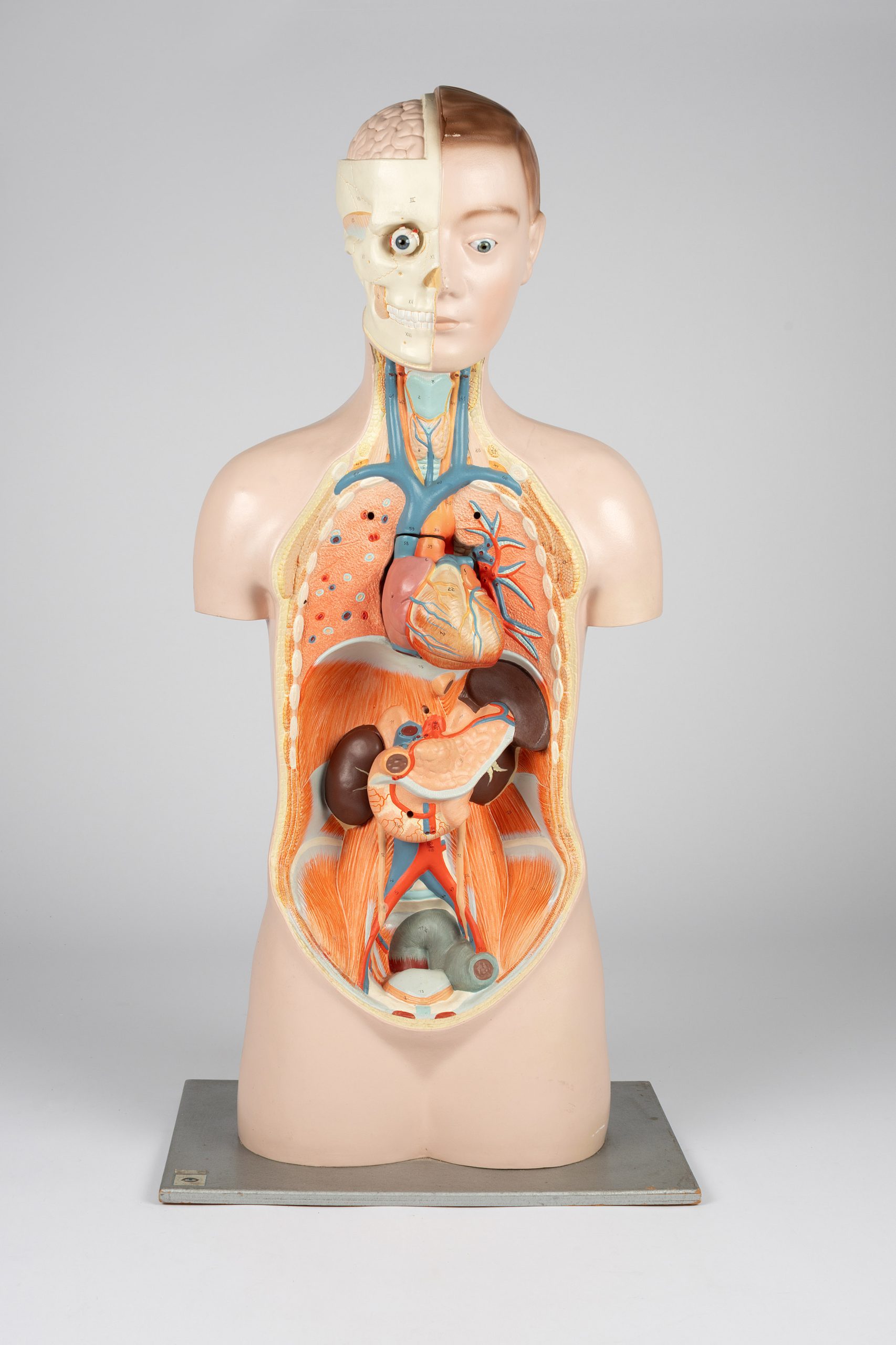

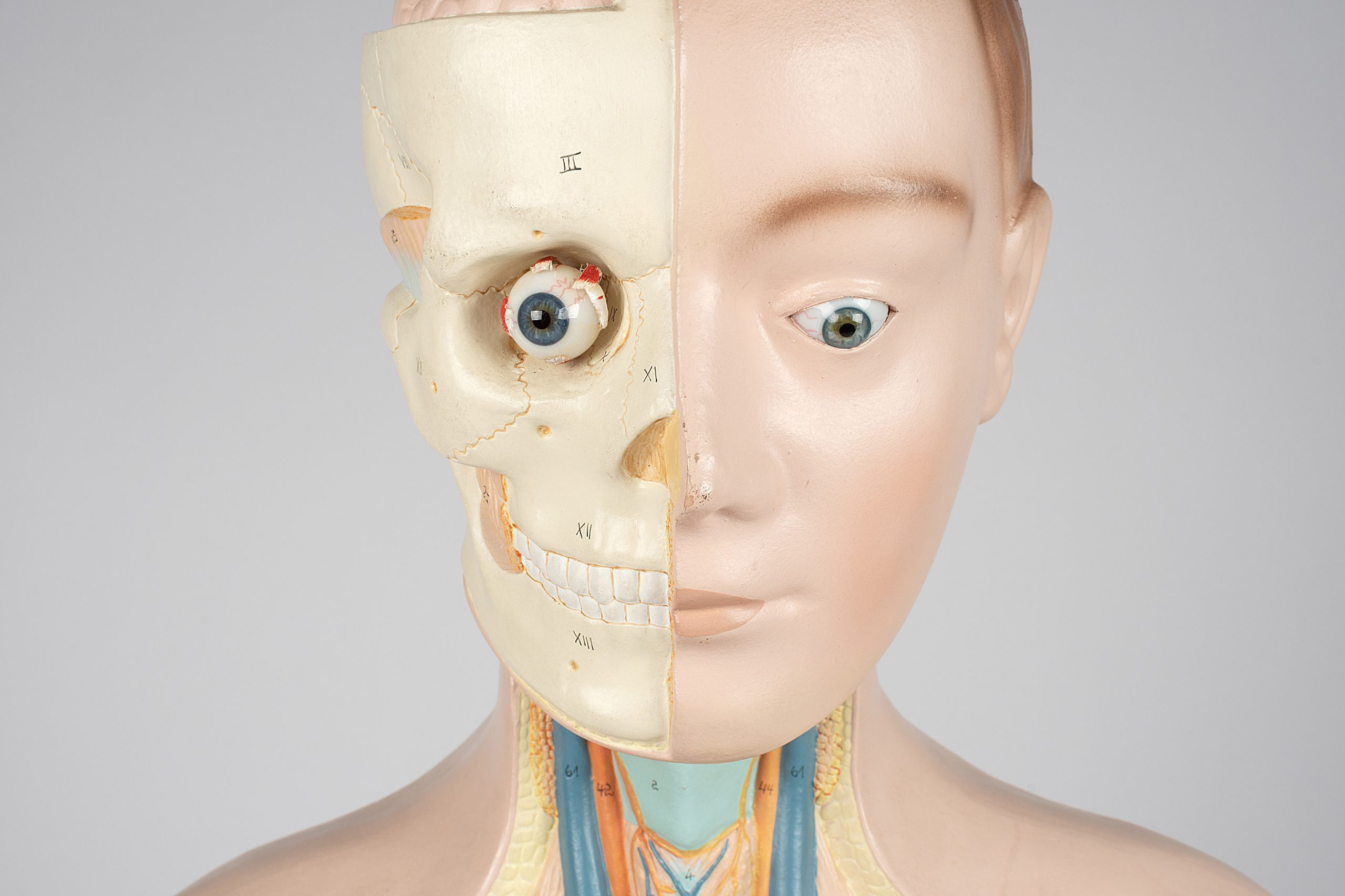

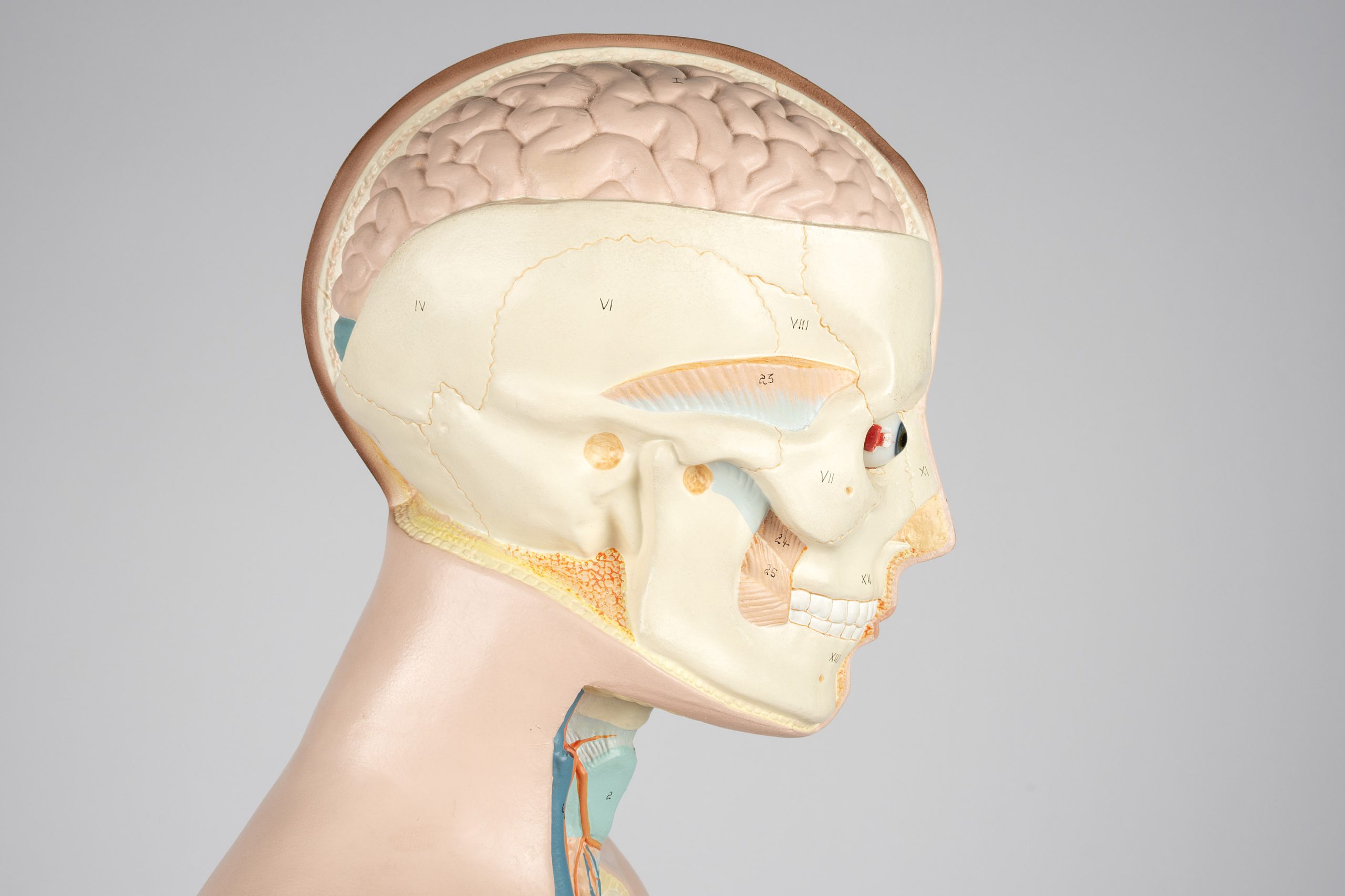

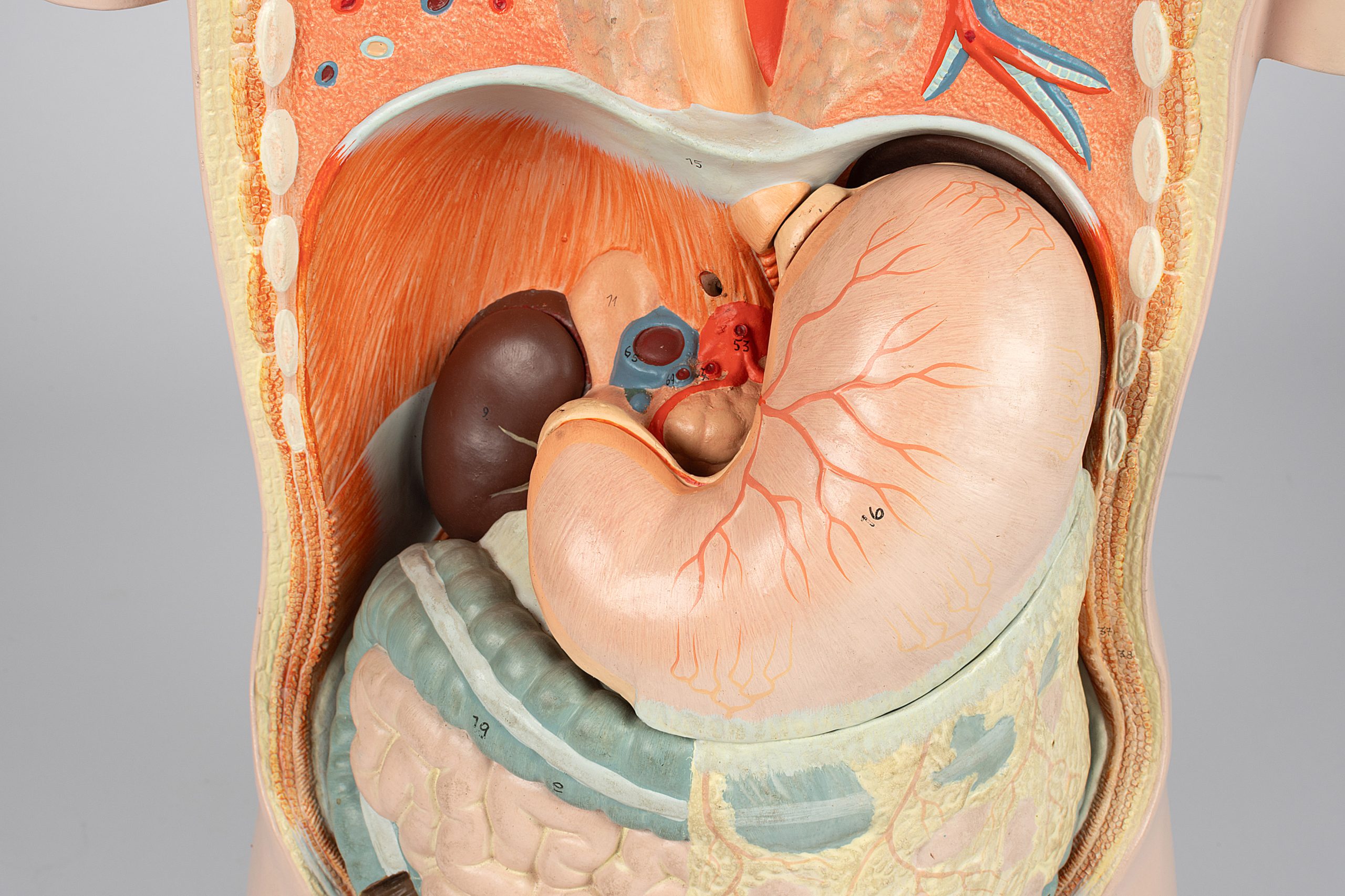

Exposed organs, popping eyeballs, and the lumpy, snaking texture of a brain might not be a sight you’d like to start the day with. However, for those in the medical profession, understanding what goes on under the skin is often essential to providing proper health care.

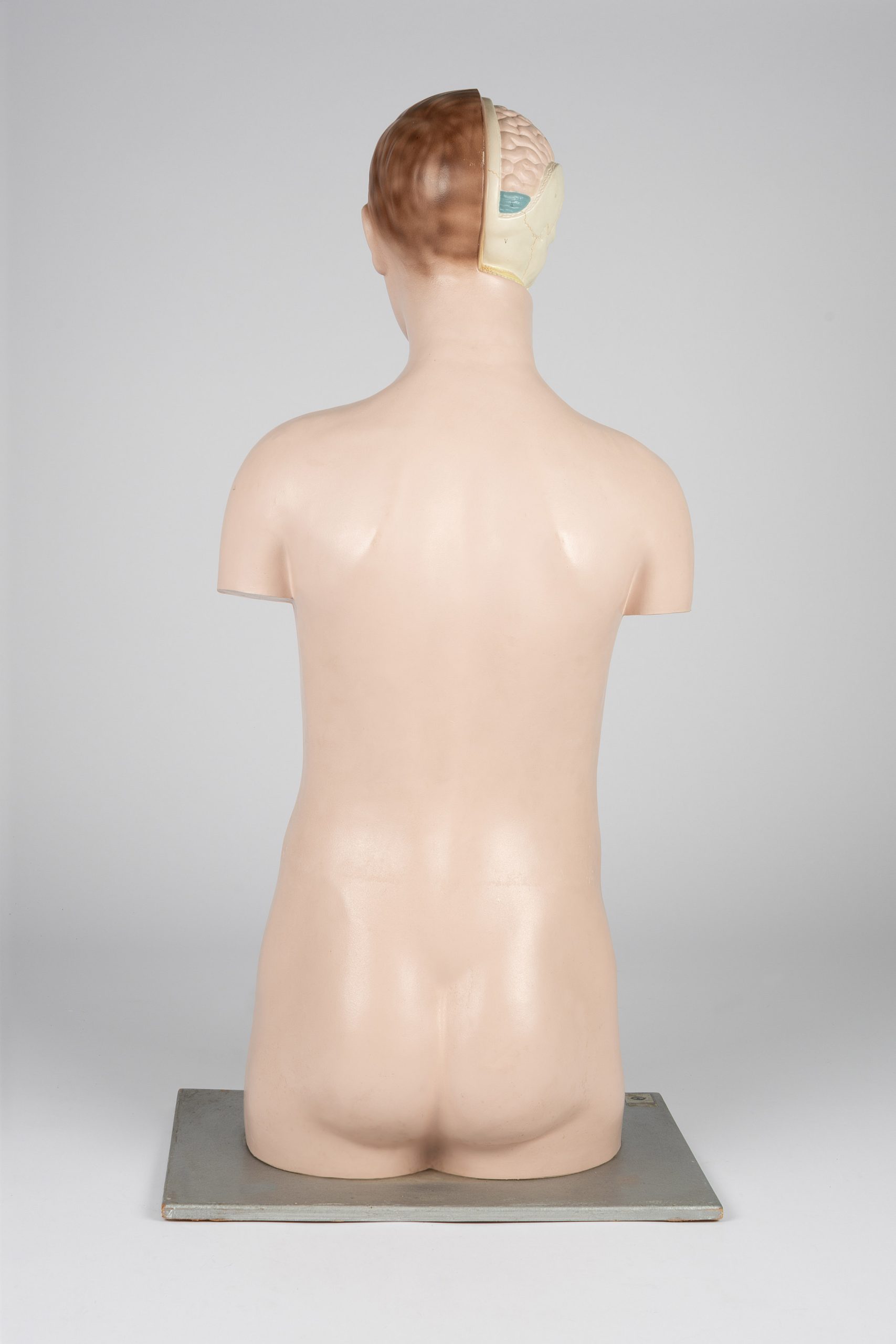

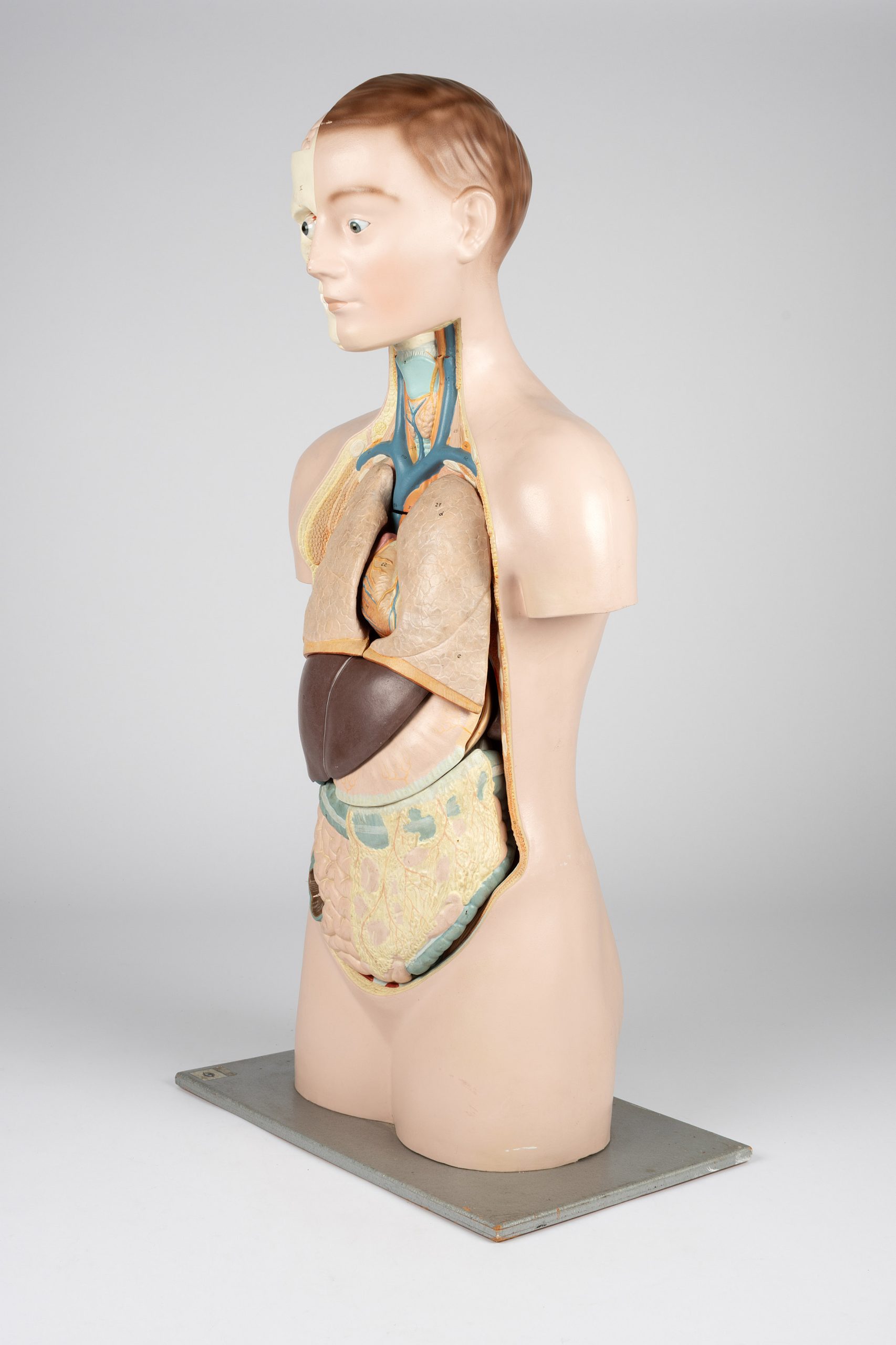

Historically, doctors often used cadavers to provide insights into human physiology. Fortunately, anatomical models like this one became popular throughout the nineteenth century, allowing hospitals to provide medical education without a need for dead bodies. This anatomical model was shipped from Germany to Australia in the mid-1900s to become an essential part of the expanding medical practice of Glen Innes, New South Wales.

Throughout the tumultuous periods of World Wars One and Two, the role of women in healthcare had shifted dynamically. In Glen Innes, women transitioned from informal midwives and care providers to indispensable members of the hospital workforce. The Glen Innes hospital expanded its facilities, adding more rooms and beds for patients, along with accommodation buildings to house the growing number of nurses and workers. Training became an integral part of the daily routine, ensuring the hospital could deliver essential services to the community.

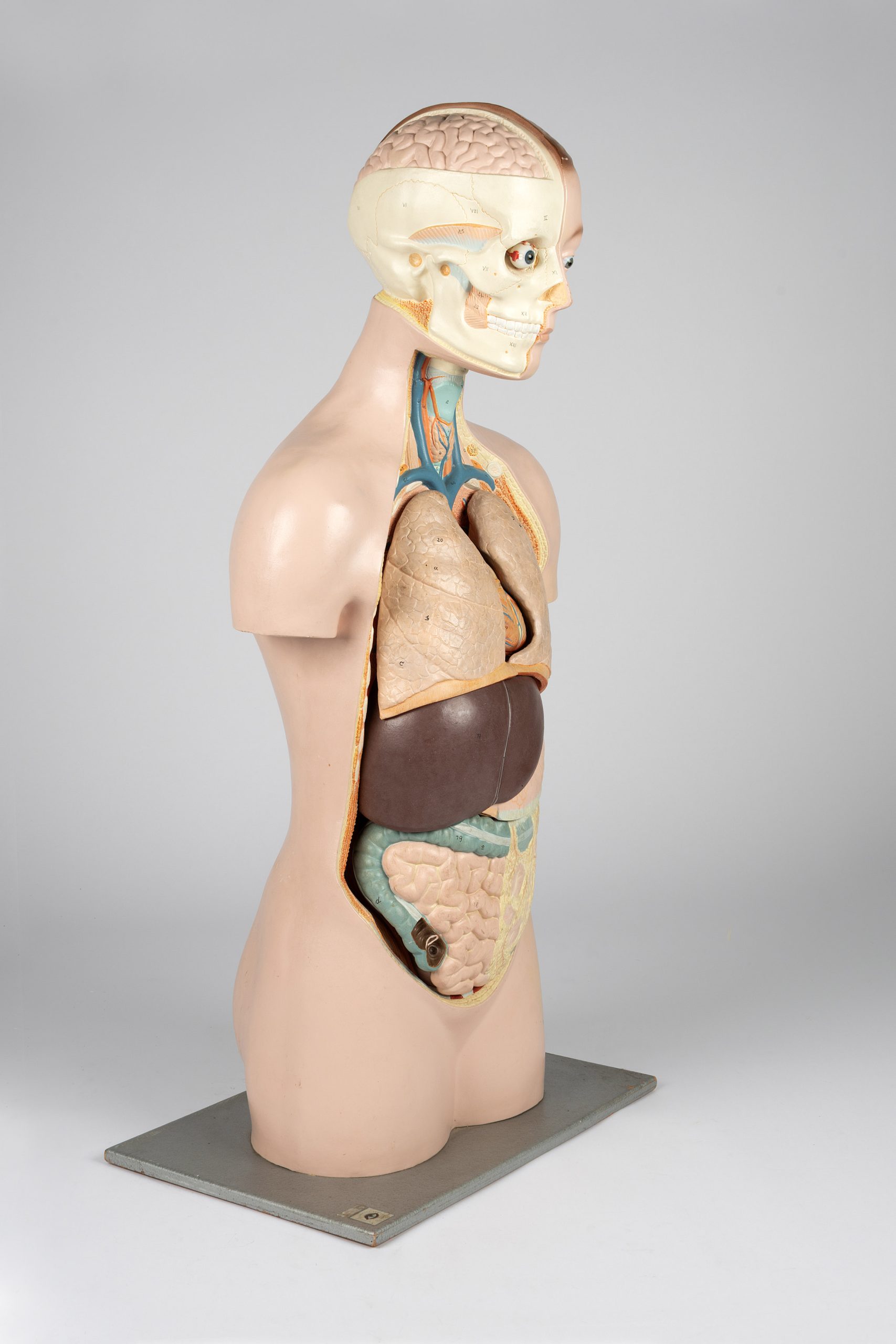

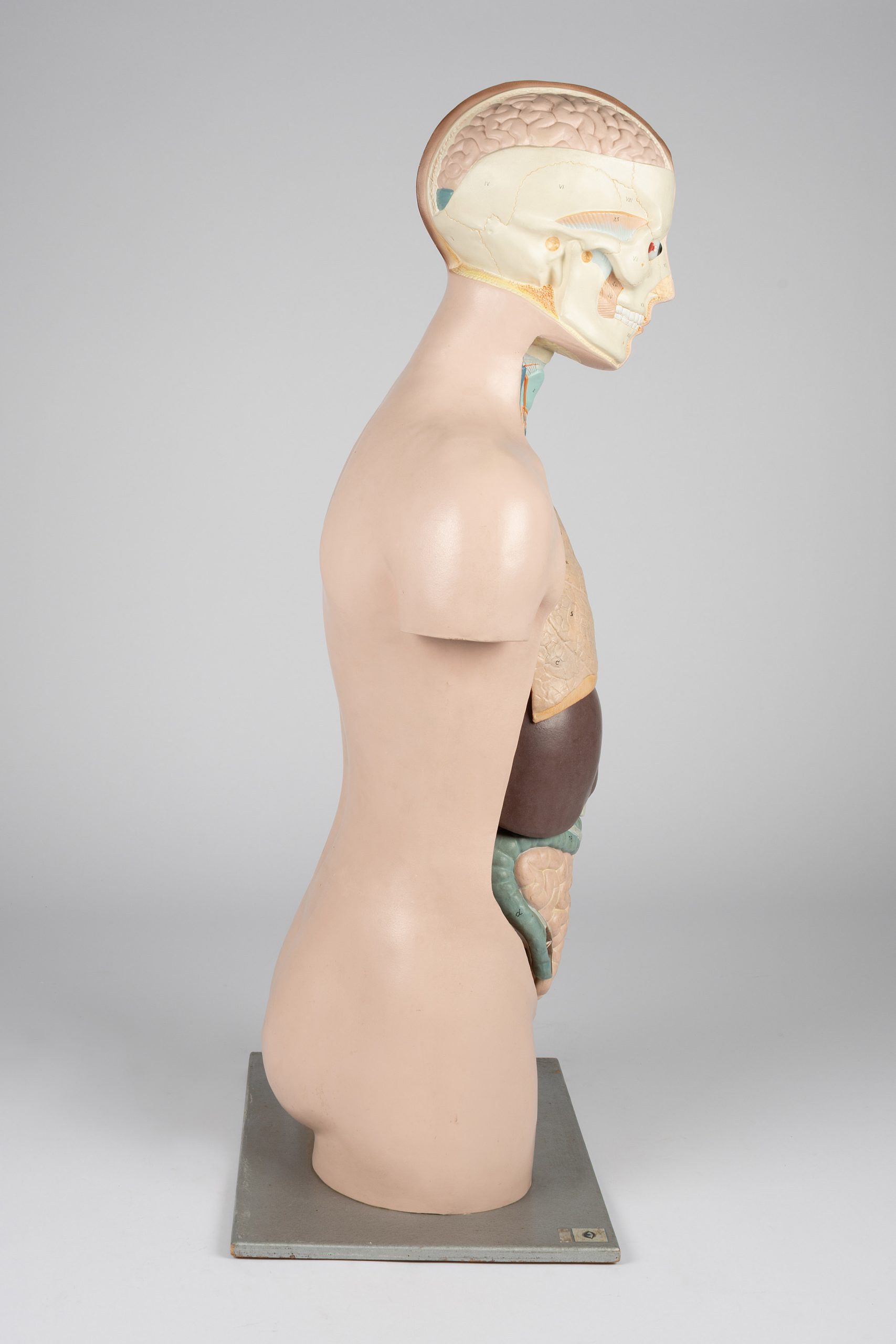

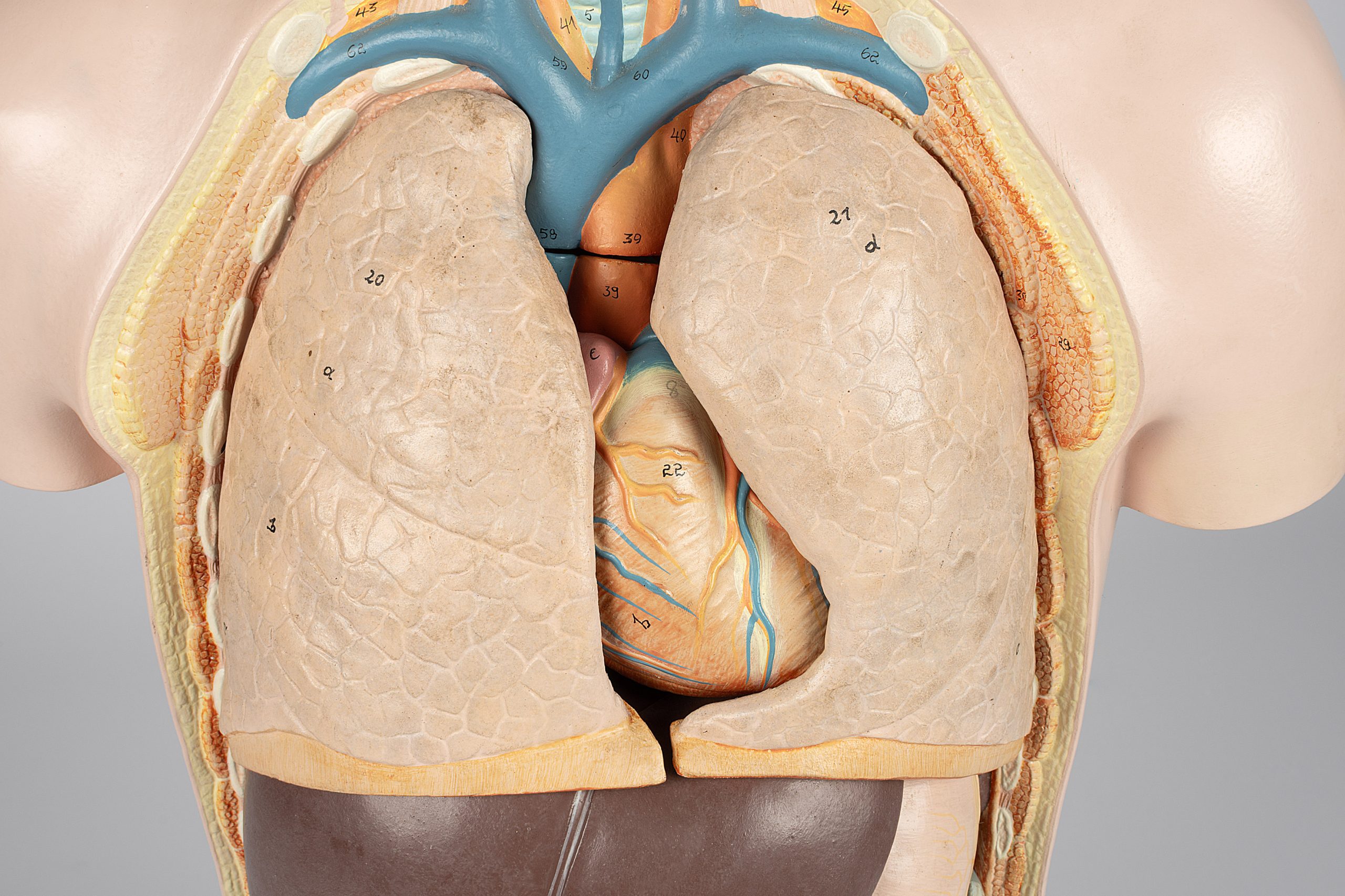

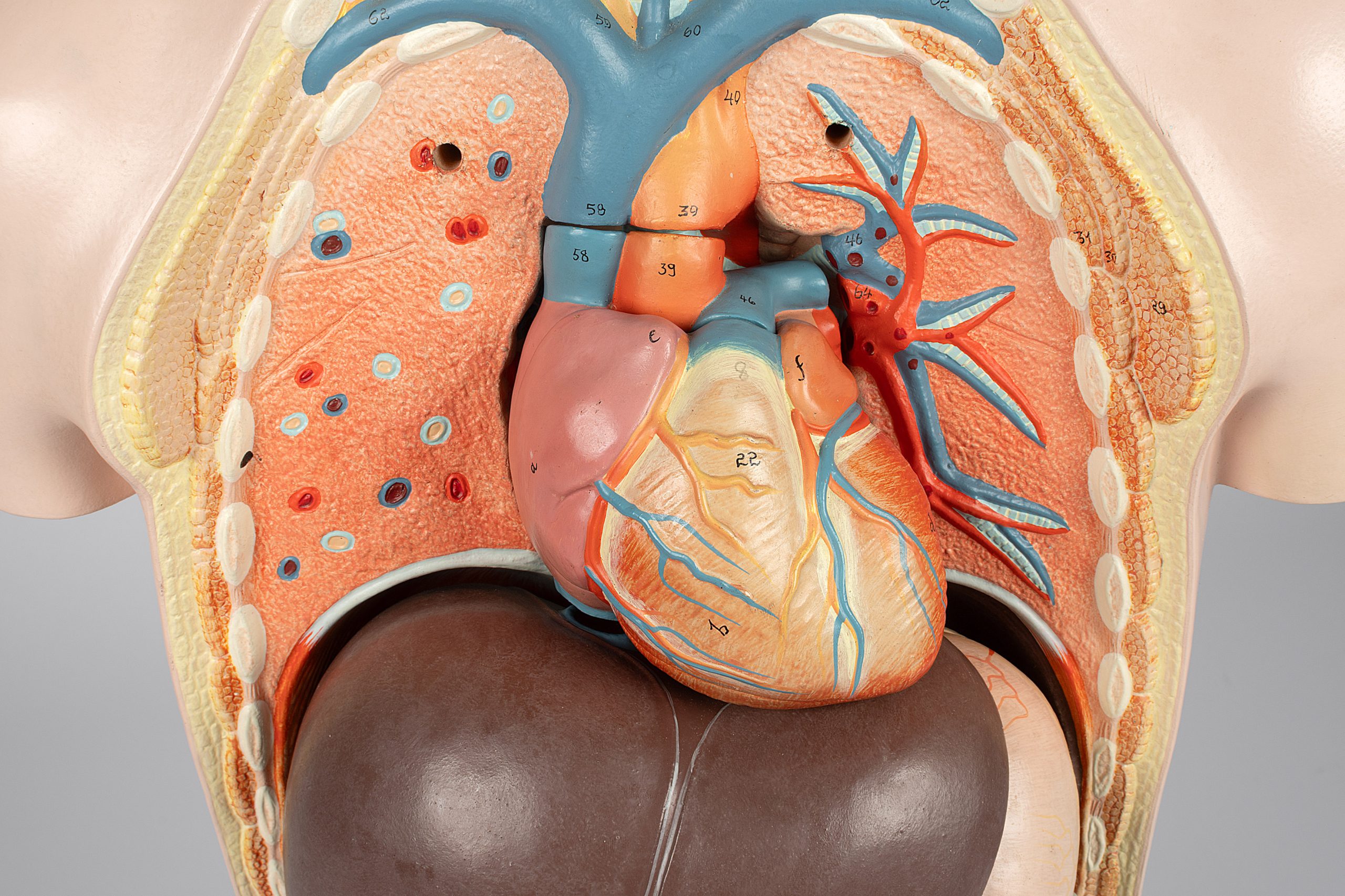

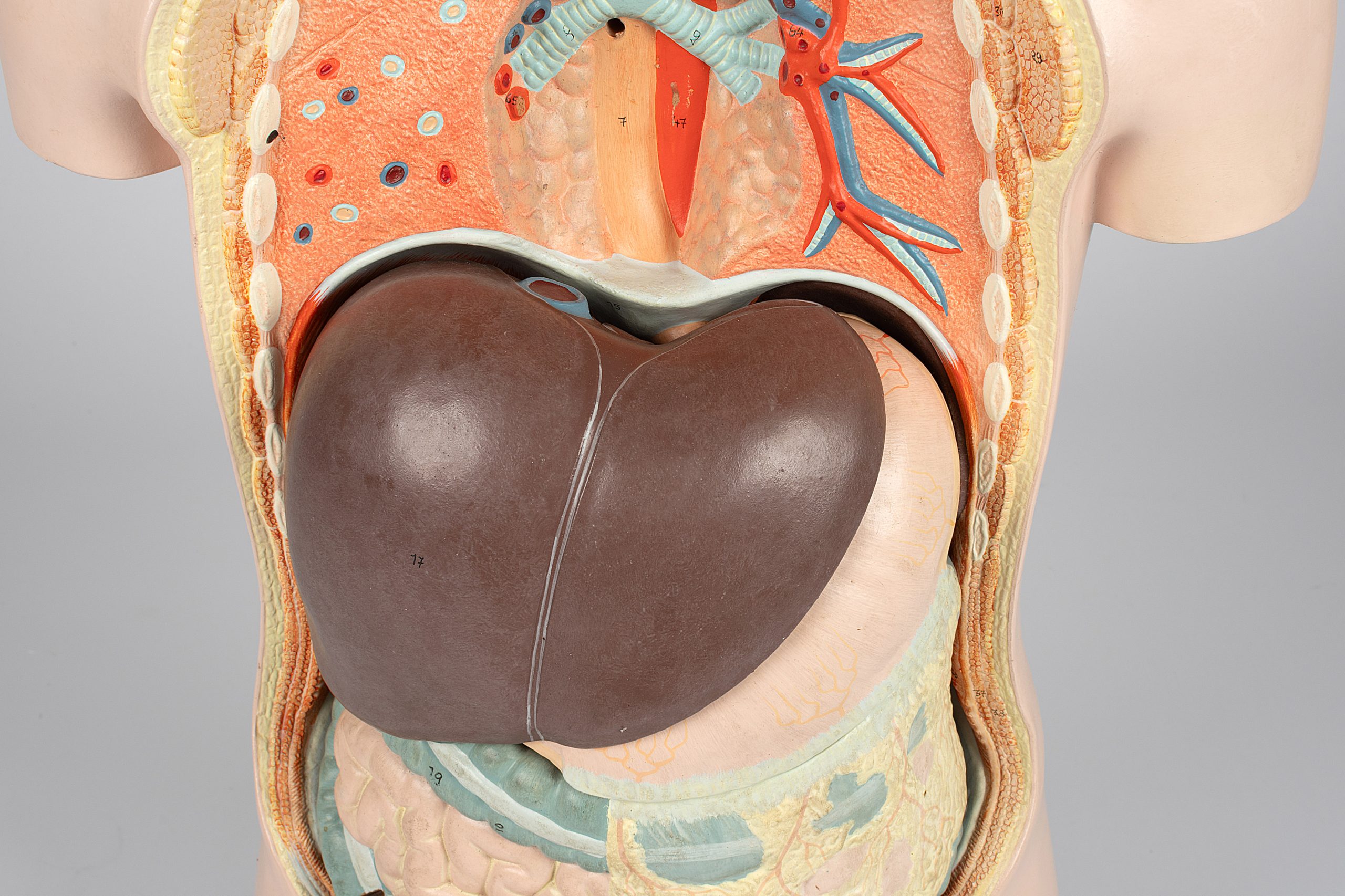

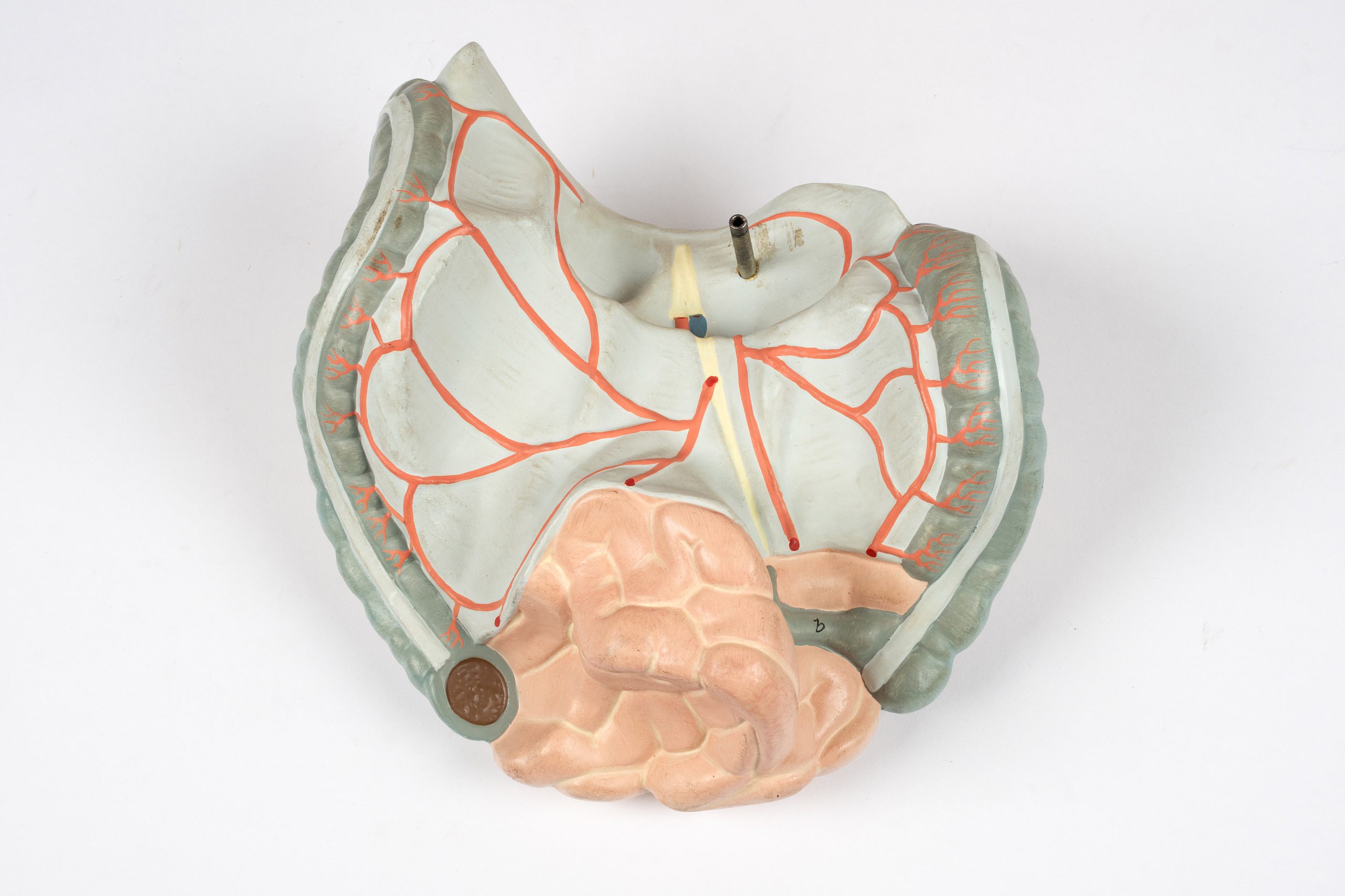

The cavity of this anatomical model features removable internal organs, which could be disassembled with precision, unveiling the intricacies of the human body. Numbered blood vessels, arteries, and a visible skull would have allowed nurses and doctors to understand how everything was meant to fit together.

While this object is in good condition, paint chips, discolouration, and loose screws are a testament to its use. Once a valuable educational tool, it bears the marks of countless students exploring the mysteries of the human form, providing a vital service to a rural community.